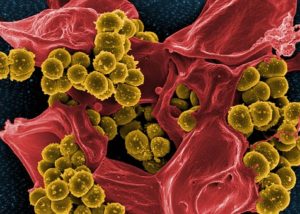

Kelsey Yamada is an MD/PhD student in Dr. Tammy Kielian’s laboratory studying Staphylococcus aureus. We enjoyed learning more about him and his work!

Tell us a little about yourself.

I am originally from Hawaii, but moved to Nebraska over a decade ago to attend Creighton University. After graduating with my B.S. Chemistry I moved to Bethesda, MD to work at the NIH. This gave me the opportunity to work along side of physician-scientists who were at the top of their fields, and ultimately helped me to decide on a career in translational medical research. My wife and I loved our time in Omaha, which led me back to Omaha and UNMCs M.D./Ph.D. program. While I am not sure what medical field I will ultimately choose, I am certain that I am interested in studying host-pathogen interactions during chronic disease.

What are you studying for your thesis, and how do you think your work will inform your future practice of medicine?

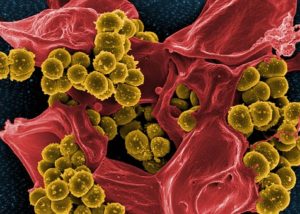

My thesis research focused on trying to understand how orthopedic implant associated S. aureus biofilms modulates the metabolism of monocytes in order to promote the establishment and persistence of infection. Though my current research is on a fairly specific ailment, it may not directly inform my clinical practice in the future (unless of course I go into orthopedics). However, I have had a lot of opportunities to work on both the clinical and basic science side of a clinical study on orthopedic implant infections. It has helped me to understand how important communication is when trying to develop and carry out a clinical study. In my future, it will be essential for me to bridge the gap between the clinical and research teams.

My thesis research focused on trying to understand how orthopedic implant associated S. aureus biofilms modulates the metabolism of monocytes in order to promote the establishment and persistence of infection. Though my current research is on a fairly specific ailment, it may not directly inform my clinical practice in the future (unless of course I go into orthopedics). However, I have had a lot of opportunities to work on both the clinical and basic science side of a clinical study on orthopedic implant infections. It has helped me to understand how important communication is when trying to develop and carry out a clinical study. In my future, it will be essential for me to bridge the gap between the clinical and research teams.

Tell us something about yourself unrelated to medicine.

I’ve watched the office from episode 1, an embarrassing number of times. But I always skip over the episodes with Will Ferrell. My friends and I demolish trivia night, unless it has to do with Deangelo Vickers and his juggling.

We’re always excited to learn about our students’ research that helps us understand problems we see all the time in clinic. If you’re interested in learning more about Kelsey’s work, check out his publications below:

Yamada, K.J., Barker, T., Dyer, K.D., Rice, T.A., Percopo, C.M., Garcia-Crespo, K.E., Cho, S., Lee, J.J., Druey, K.M., Rosenberg, H.F. Eosinophil-associated Ribonuclease 11 is a Macrophage Chemoattractant. J. Biol. Chem., 290:8863-8875, 2015. PMID: 25713137

Yamada, K.J., Heim, C.E., Aldrich, A.L., Gries, C.M., Staudacher, A.G., Kielian, T. Arginase-1 Expression in Myeloid Cells Regulates Staphylococcus aureus Planktonic but Not Biofilm Infection. Infect Immun. 86:e206-218, 2018. PMID: 29661929

Yamada, K.J., Kielian, T. Biofilm-Leukocyte Cross-Talk: Impact on Immune Polarization and Immunometabolism. J. Innate Immun., 2018. PMID: 30347401

Zhou, C., Bhinderwala, F., Lehman, M.K., Thomas, V.C., Chaudhari, S.S., Yamada, K.J., Powers, R., Kielian, T., Fey, P.D. Urease is an essential component of the acid response network of Staphylococcus aureus and is required for a persistent murine kidney infection. PLoS Pathog., 2018. PMID: 30608981

Yamada, K.J., Xi, X., Attri, K.S., Zhang, W., Singh, P.K., Bronich, T.K., Kielian, T. Nanoparticle targeting of monocyte metabolism to treat Staphylococcus aureus prosthetic joint infection. (In revision at Journal of immunology).

Lehman, M.K., Nuxoll, A.S., Yamada, K.J., Kielian, T., Carson, S.D., Fey, P.D. Protease-mediated growth of Staphylococcus aureus on host proteins is opp3-dependent. (In submission to mBio).

This is yet another study demonstrating the ease of implementation of checklists/bundles for improving quality of patient care.

This is yet another study demonstrating the ease of implementation of checklists/bundles for improving quality of patient care.

As Dr. Cawcutt wrote in her review, “De-escalation in culture-negative pneumonia may result in lower AKI and ICU and hospital LOS. There is clear potential benefit for patients and overall health care systems in advocating for earlier de-escalation, regardless of whether or not nares swabs were completed.”

As Dr. Cawcutt wrote in her review, “De-escalation in culture-negative pneumonia may result in lower AKI and ICU and hospital LOS. There is clear potential benefit for patients and overall health care systems in advocating for earlier de-escalation, regardless of whether or not nares swabs were completed.”

My thesis research focused on trying to understand how orthopedic implant associated S. aureus biofilms modulates the metabolism of monocytes in order to promote the establishment and persistence of infection. Though my current research is on a fairly specific ailment, it may not directly inform my clinical practice in the future (unless of course I go into orthopedics). However, I have had a lot of opportunities to work on both the clinical and basic science side of a clinical study on orthopedic implant infections. It has helped me to understand how important communication is when trying to develop and carry out a clinical study. In my future, it will be essential for me to bridge the gap between the clinical and research teams.

My thesis research focused on trying to understand how orthopedic implant associated S. aureus biofilms modulates the metabolism of monocytes in order to promote the establishment and persistence of infection. Though my current research is on a fairly specific ailment, it may not directly inform my clinical practice in the future (unless of course I go into orthopedics). However, I have had a lot of opportunities to work on both the clinical and basic science side of a clinical study on orthopedic implant infections. It has helped me to understand how important communication is when trying to develop and carry out a clinical study. In my future, it will be essential for me to bridge the gap between the clinical and research teams.

Recent Comments