Content by Dr. Clayton Mowrer, 2021 UNMC ID graduate.

Early in the pandemic, it became clear that patients with COVID-19 can demonstrate prolonged detection of viral RNA (as along as weeks to months), which can lead to prolonged hospitalizations, especially for those patients with more severe disease. One of the difficulties often encountered in managing these patients was in determining how long they were required to be in isolation. Initially, the policy for removal of isolation at UNMC involved two sequential negative molecular testing 24 hours apart. However, after studies surfaced demonstrating the probability of isolating replication-competent SARS-CoV-2 virus was rare after 14 days of illness and at cycle-threshold (Ct) values greater than 30, UNMC revised our policy to reflect a conservative approach based on these findings. In June 2020, the revised policy stated that, in a patient who continues to test positive, isolation precautions could be removed 21 days after 1st positive test after review by the COVID ID team.

In this study recently published in Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology, we set out to:

- Evaluate UNMC de-isolation policy

- Describe the clinical characteristics of these patients

- Describe the Ct values

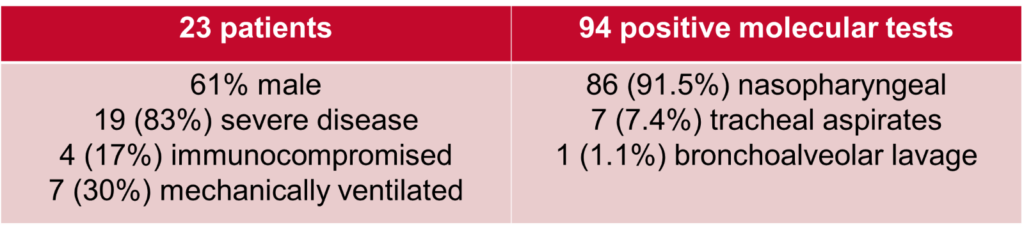

We performed a retrospective study of adult hospitalized patients with persistently positive SARS-CoV-2 molecular testing who were removed from isolation after 21 days from their first positive test. Of the 23 patients we evaluated, we found that 4 (17%) of patients were considered to be immunocompromised. 19 (83%) of patients were considered to have severe disease (per NIH criteria), with 7 (30%) still mechanically ventilated.

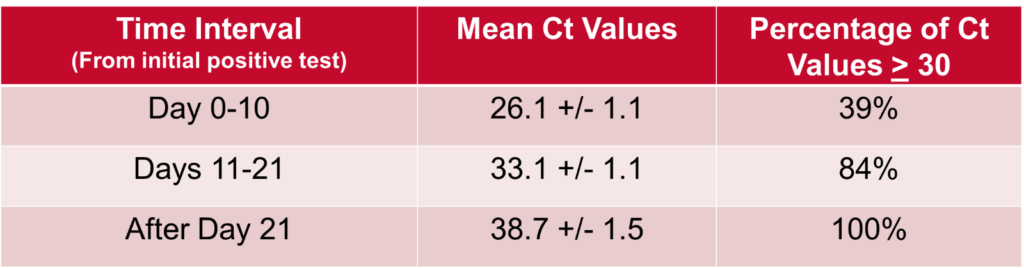

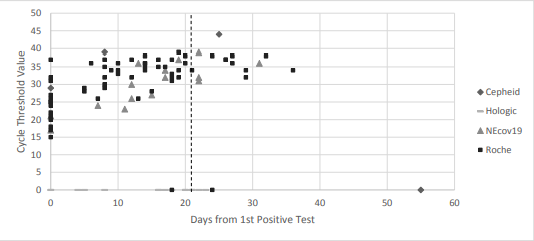

With regards to the Ct values, we compiled and evaluated 94 total tests these 23 patients. We found that, as demonstrated in the below table and figure, Ct values showed a general upwards trend over time and that there was a statistically significant difference in the mean Ct values between time interval. All Ct values after 21 days from first positive test were shown to be >30.

These findings, combined with the fact that no cases of transmission within our healthcare system have been linked to patients who have been removed from isolation at day 21, suggest that our 21-day de-isolation policy – which utilizes clinical criteria in conjunction with ID expert consultation – is a reasonable and safe approach. Furthermore, the Ct value, indeed, may be a useful addition in the overall assessment.

Read the full article here.

undefined

Recent Comments