Every month, we have a faculty member presents their ongoing research. Last month we had the opportunity to learn from Dean Bradley Britigan about novel antimicrobial strategies involving disruption of bacterial iron metabolism. Microorganisms need iron for growth and metabolism; they need it for enzymes, gene regulation, and development of virulence factors. Most bacterial species requiring iron for metabolism secrete siderophores which are low molecular weight proteins that facilitate iron uptake into the cells.

Every month, we have a faculty member presents their ongoing research. Last month we had the opportunity to learn from Dean Bradley Britigan about novel antimicrobial strategies involving disruption of bacterial iron metabolism. Microorganisms need iron for growth and metabolism; they need it for enzymes, gene regulation, and development of virulence factors. Most bacterial species requiring iron for metabolism secrete siderophores which are low molecular weight proteins that facilitate iron uptake into the cells.

Trojan Horse

Trojan Horse

Dr. Britigan shared that both Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Francisella tularensis are intracellular pathogens of macrophages that produce siderophores for iron-mediated pathogenesis. In the age of increasing antimicrobial resistance, Dr. Britigan’s work has been dedicated to investigating whether bacterial iron metabolism can be targeted as a novel antimicrobial approach to therapy. They have found some interesting results using gallium as a “Trojan horse”.

Gallium is a trivalent cation with similar size, binding/affinity and molecular properties as a trivalent iron cation, however unlike iron, it cannot be reduced to a divalent state under physiologic conditions; therefore when gallium is substituted for iron in iron-containing enzymes they cease to function. If they saturate the bacterium’s environment with gallium, they can essentially “trick” it into believing it has iron, when it doesn’t. The ability of gallium to disrupt cancer cell iron metabolism via a similar mechanism of action in humans led to FDA approval of gallium nitrate for the treatment of hypercalcemia in malignancy. Early studies showed that gallium inhibited the growth of M. tuberculosis and F. tularensis in macrophages, and reduced the amount of intracellular iron within these bacteria in a concentration-dependent fashion. The inhibitory effect was found to be reversible when extracellular concentrations of iron were increased. In murine models infected with F. tularensis and M. tuberculosis, the overwhelming majority of mice survived infection when treated with gallium.

Cystic Fibrosis

This concept was then applied to Pseudomonas aeruginosa, with particular interest in the cystic fibrosis patient population due to growing antimicrobial resistance and biofilm production. Dr. Britigan’s team in collaboration with investigators at the University of Washington found that gallium also inhibited growth of P. aeruginosa in the murine models of pseudomonas infection, and most mice survived infection with this organism (unless there was significant iron levels in the environment). Remarkably, gallium also inhibited the formation of P. aeruginosa biofilm, with high concentrations killing bacteria within the interior of the biofilm. The mechanism of action for biofilm inhibition has not been fully determined, but they hypothesized that there may be multiple sites of action of the gallium. This hypothesis was tested in vitro with multiple iron-dependent bacterial enzymes including catalase, superoxide dismutase and ribonucleotide reductase, found to be inhibited by the presence of gallium in growth media.

This work has generated enough interest for clinical trials. In the phase 1 trial, the drug appeared to be well tolerated; the phase 2 trial results have not been released. Dr. Britigan’s lab is continuing to look at clinical isolates before and after treatment with gallium to evaluate for changes in resistance patterns as a result of this treatment, and studies are still ongoing. If applied to clinical practice, gallium would be given intravenously (FDA approved in this form). It’s half-life in the lung is approximately 48-72hrs, and in serum 24hrs, but is not a good candidate for oral formulation as it stands as it is not well absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract. In the cystic fibrosis population the inhaled formulation would be preferred, but studies of the drug in this form are ongoing.

Future Clinical Applications

The clinical application of gallium in bacterial infections would be complementary to the traditional antimicrobials. Gallium is bacteriostatic, which means it inhibits growth rather than kills bacteria. A theory of bacterial resistance mechanisms in biofilm-producing organisms is that the antibiotic cannot penetrate the biofilm adequately, therefore bacteria on inner layers can become resistant. Gallium synergy would be useful here, because its inhibitory effects extend to biofilm; it can help to penetrate biofilm, reduce bacterial burden and create an environment where bactericidal antibiotics can work more effectively to kill bacteria. Future directions and questions would be to define the forms of gallium that are most effective against target organisms, and expand to include evaluation of additional resistant organisms (e.g. M. abscessus), identify novel drug delivery options (e.g. nanoparticle aerosol delivery), or viral organisms (HIV/TB co-infections).

Teaching Old Drugs New Tricks

In an age where antimicrobial resistance is inevitable, it is a relief to hear about physician-scientists thinking outside the box when it comes to development of antimicrobial agents. Brand new drug development is important but can take up to 10 years along the continuum of drug idea to testing, to FDA approval, to clinical availability. For many of these resistant infections, we may not have 10 years to wait for this process, and this is where re-purposing “old” drugs can be helpful to bridge the gap.

Content Acknowledgement: Thanks to Dr. Bradley Britigan

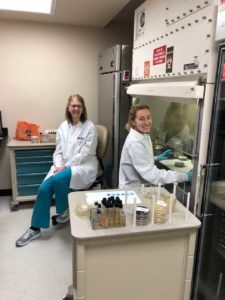

If you work in an office at all, chances are you have come into contact with an Administrative Professional. The impact of an Administrative Professional on their office team has been compared to glue or paperclips that keep the office together. Our Administrative Professionals are an integral part of our group here at UNMC ID. Sure, they help with things like setting up meetings, lectures, organizing receipts and appointments; but the best part of our people here are the intangibles. These individuals are so well integrated into our daily routines that it can be easy to take them for granted, but if they are absent for some reason, it becomes more obvious to us how much we rely on them for our days to go smoothly. In addition to the administrative duties, our Administrative Professionals are like family. They routinely visit our faculty and fellows to say hi, to check in with us to make sure we are staying sane, help new faculty and staff get acclimated, organize collections of food and money to help our colleagues in the division during difficult

If you work in an office at all, chances are you have come into contact with an Administrative Professional. The impact of an Administrative Professional on their office team has been compared to glue or paperclips that keep the office together. Our Administrative Professionals are an integral part of our group here at UNMC ID. Sure, they help with things like setting up meetings, lectures, organizing receipts and appointments; but the best part of our people here are the intangibles. These individuals are so well integrated into our daily routines that it can be easy to take them for granted, but if they are absent for some reason, it becomes more obvious to us how much we rely on them for our days to go smoothly. In addition to the administrative duties, our Administrative Professionals are like family. They routinely visit our faculty and fellows to say hi, to check in with us to make sure we are staying sane, help new faculty and staff get acclimated, organize collections of food and money to help our colleagues in the division during difficult  times, celebrate our birthdays and achievements, and give hugs or hold our hands when we have losses or disappointments. They do all of these things without ever asking for recognition.

times, celebrate our birthdays and achievements, and give hugs or hold our hands when we have losses or disappointments. They do all of these things without ever asking for recognition. What is meningitis?

What is meningitis?

Every month, we have a faculty member presents their ongoing research. Last month we had the opportunity to learn from Dean Bradley Britigan about novel antimicrobial strategies involving disruption of bacterial iron metabolism. Microorganisms need iron for growth and metabolism; they need it for enzymes, gene regulation, and development of virulence factors. Most bacterial species requiring iron for metabolism secrete siderophores which are low molecular weight proteins that facilitate iron uptake into the cells.

Every month, we have a faculty member presents their ongoing research. Last month we had the opportunity to learn from Dean Bradley Britigan about novel antimicrobial strategies involving disruption of bacterial iron metabolism. Microorganisms need iron for growth and metabolism; they need it for enzymes, gene regulation, and development of virulence factors. Most bacterial species requiring iron for metabolism secrete siderophores which are low molecular weight proteins that facilitate iron uptake into the cells. Trojan Horse

Trojan Horse

Recent Comments