As faculty, we have the amazing opportunity to both mentor and interview residents applying for fellowship in Infectious Diseases, and we have seen it all. From the great, well-prepared interviewee to the one who had the institutional information completely incorrect. We wish we could mentor every resident in person, but since that is not possible, we decided to do the next best thing and offer our tips and tricks to acing the ID (or any other) interview! Tips and tricks are in no particular order.

- Be yourself and relax.

- Articulate why you are interested in this fellowship program, what your ID interests are and where you think you would like your career to go (even if you acknowledge that might change or be a little vague at this time).

- Have an idea of how the program works and ask specific questions to help deepen that knowledge regarding the education you will receive. What are the strengths, weakness and unique aspects of the program you want to know more about?

- Remember that you are interviewing the fellowship program as much as they are interviewing you. Do your research and come prepared with questions about everything from how the fellowship will prepare you for your career as an ID physician to where you will park.

- Need suggestions on how to curate your list of questions?

- Look up the program and Division on their website.

- It is helpful to know a little about the faculty you are interviewing with, so if you get a schedule ahead of time find out what their clinical/research interests are and ask them about it – you can check out their publications on PubMed or Google Scholar to focus questions on specific topics. If you don’t get a schedule ahead of time, ask them what their interests are or what their role is during your interview.

- Formulate questions important to you about the program, the institution and the local area regarding resources, lifestyle and more.

- Need suggestions on how to curate your list of questions?

- Be prepared to talk about your successes and the challenges you have encountered. For example, if you have an unexpected break in training, use that as example to illustrate what you learned from that experience. We do not expect perfection, but value honesty and clarity.

- If you have something on your application that might be viewed negatively (academic difficulties, etc.) take the initiative and explain how you have overcome it and why you are a good candidate now before we have to ask you about it.

- Consider a “highlight” reel handout for faculty on an updates to your CV since you submitted your application in ERAS. This can be incredibly beneficial if you have had a new publication, presentation or other activities demonstrating your interest in ID and future potential as a fellow.

- Be friendly and treat everyone, including program coordinators and other office personnel kindly and with respect. Your interview starts from the moment some first meets you (a current fellow, administrative assistant or staff) and ends when you say goodbye to the last person. ALL opinions count. If you are rude to anyone, trust us, we will find out.

- Be truthful and be yourself. Don’t answer questions with what you think the interviewer wants to hear (e.g. don’t say you want to do academic medicine if you are interested in private practice). This is the only way for both you and the program to determine whether or not you are truly a good fit.

- Tell us something interesting about yourself, even if it doesn’t relate to ID. It is important to be well-rounded, and hearing about hobbies, experiences and interests helps keep the interview conversation fun and flowing.

- Thank the faculty for their time; the emails and cards with a personal comment regarding a specific detail of the interview are both appreciated and noticed.

Multiple ID faculty contributed to this list and thus the credit goes to the entire UNMC Division.

In the second article, the authors reported a case of

In the second article, the authors reported a case of

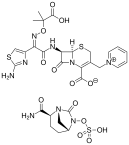

Meanwhile, given the slow drug discovery pipeline, modification of our current use patterns and Antimicrobial Stewardship still remain the cornerstone strategies to prevent us from toppling off the proverbial cliff of antimicrobial resistance.

Meanwhile, given the slow drug discovery pipeline, modification of our current use patterns and Antimicrobial Stewardship still remain the cornerstone strategies to prevent us from toppling off the proverbial cliff of antimicrobial resistance.

I’m the first doctor in my family. I was born in the California’s San Joaquin Valley and spent most of my life there. My fondest memories growing up were travelling around the state playing (and winning of course) soccer, going deep into the Sierra Nevadas on camping and fishing trips and spending time at my grandfather’s ranch (now a peach farm that I’m excited to say should produce its first crop this year).

I’m the first doctor in my family. I was born in the California’s San Joaquin Valley and spent most of my life there. My fondest memories growing up were travelling around the state playing (and winning of course) soccer, going deep into the Sierra Nevadas on camping and fishing trips and spending time at my grandfather’s ranch (now a peach farm that I’m excited to say should produce its first crop this year). Google Maps and type in

Google Maps and type in  Most intra-abdominal abscesses are polymicrobial. Sometimes aerobic organisms are identified from culture, but often anaerobic organisms do not grow on conventional culture media, especially when patients have received prior antibiotics. This knowledge often leads to broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy including anaerobic coverage.

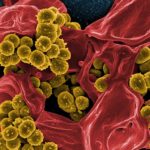

Most intra-abdominal abscesses are polymicrobial. Sometimes aerobic organisms are identified from culture, but often anaerobic organisms do not grow on conventional culture media, especially when patients have received prior antibiotics. This knowledge often leads to broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy including anaerobic coverage. They included 26 samples with amplification products and deep sequenced them. 8 of these samples were gram stain and culture negative, and while these had lower microbial diversity, bacterial sequences revealed a predominance of streptococci, B. fragilis and gram positive anaerobic cocci.

They included 26 samples with amplification products and deep sequenced them. 8 of these samples were gram stain and culture negative, and while these had lower microbial diversity, bacterial sequences revealed a predominance of streptococci, B. fragilis and gram positive anaerobic cocci. The biggest limitation is that with the samples being de-identified, there is no patient-level antimicrobial history data to correlate and account for culture growth. We also don’t have treatment and outcomes data after the cultures were obtained, so it is not clear whether or not the targeted therapy for a monomicrobial abscess culture resulted in clinical cure; in which case, what difference does it make to know about these other organisms?

The biggest limitation is that with the samples being de-identified, there is no patient-level antimicrobial history data to correlate and account for culture growth. We also don’t have treatment and outcomes data after the cultures were obtained, so it is not clear whether or not the targeted therapy for a monomicrobial abscess culture resulted in clinical cure; in which case, what difference does it make to know about these other organisms?

The following is a review by one of our fellows

The following is a review by one of our fellows  accumulating slowly.

accumulating slowly. Based on the beta-lactam allergy history 50% of the patients received preferred beta-lactam agents during the baseline period. This number was increased to 60% during intervention period by careful evaluation by ASP team by history alone (P = .02). During the intervention period after implementation of BLAST, use of preferred beta lactam therapy further increased to 81% (P < .001). The authors concluded there were 4.5-folds higher odds of receiving preferred beta lactam therapy after implementation of BLAST without increase in side effects (95% CI, 2.4–8.2; P < .0001). During the intervention period use of agents with higher risk for C difficile infection such as fluoroquinolones and carbapenems decreased more than half (28% vs 13%; P < .0002) and penicillin use tripled (11% vs 32%; P < .0002).

Based on the beta-lactam allergy history 50% of the patients received preferred beta-lactam agents during the baseline period. This number was increased to 60% during intervention period by careful evaluation by ASP team by history alone (P = .02). During the intervention period after implementation of BLAST, use of preferred beta lactam therapy further increased to 81% (P < .001). The authors concluded there were 4.5-folds higher odds of receiving preferred beta lactam therapy after implementation of BLAST without increase in side effects (95% CI, 2.4–8.2; P < .0001). During the intervention period use of agents with higher risk for C difficile infection such as fluoroquinolones and carbapenems decreased more than half (28% vs 13%; P < .0002) and penicillin use tripled (11% vs 32%; P < .0002).

Given the improvement in use of beta-lactams with just more intensive allergy history-taking, is the cost-effective solution simply just

Given the improvement in use of beta-lactams with just more intensive allergy history-taking, is the cost-effective solution simply just

Olivia: During my studies at UNL, I became interested in underserved communities after volunteering at the People’s City Mission (PCM) free health clinic. While at PCM, I interacted with patients who fell through the cracks in our healthcare system, a system that I have always been able to access. Soon after, I began to recognize disparity in my hometown of Columbus, NE in patients living in rural areas who struggle to meet with urban specialists to manage their health problems. Furthermore, my major of Global Studies took me to Mumbai, India where I met patients diagnosed with epilepsy who faced a great deal of social stigma surrounding their disease.

Olivia: During my studies at UNL, I became interested in underserved communities after volunteering at the People’s City Mission (PCM) free health clinic. While at PCM, I interacted with patients who fell through the cracks in our healthcare system, a system that I have always been able to access. Soon after, I began to recognize disparity in my hometown of Columbus, NE in patients living in rural areas who struggle to meet with urban specialists to manage their health problems. Furthermore, my major of Global Studies took me to Mumbai, India where I met patients diagnosed with epilepsy who faced a great deal of social stigma surrounding their disease. Rohan: My interest in health disparities largely stems from the time I spent as an undergraduate in St. Louis. Following the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, a neighborhood 10-15 minutes from where I lived at the time, I became acutely aware that St. Louis, like Omaha, is a city with historically ingrained divisions that create disparities in the social determinants of its citizens’ health. I was inspired by the widespread activism I saw around St. Louis and involved myself in a narrative-based music outreach program to help uplift the stories of young community members. I was also motivated to leverage my own leadership positions on campus to advocate for the mental health of students of color and LGBTQ+ students.

Rohan: My interest in health disparities largely stems from the time I spent as an undergraduate in St. Louis. Following the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, a neighborhood 10-15 minutes from where I lived at the time, I became acutely aware that St. Louis, like Omaha, is a city with historically ingrained divisions that create disparities in the social determinants of its citizens’ health. I was inspired by the widespread activism I saw around St. Louis and involved myself in a narrative-based music outreach program to help uplift the stories of young community members. I was also motivated to leverage my own leadership positions on campus to advocate for the mental health of students of color and LGBTQ+ students. Laura: Through volunteering at community organizations growing up, I became aware of differences in wealth, educational opportunities, and neighborhood resources between Omaha communities. During a college course in Ecuador which focused on social and political transformations, I gained a broader understanding of the global pervasiveness of inequalities, especially in health. In Minnesota where I attended college, I volunteered at a community health clinic teaching an exercise and nutrition class for Hispanic and Somali women struggling with obesity and diabetes. The hard work, persistence, and camaraderie of these women left me inspired and grateful for their friendship and the privilege to take part in their path to better health, and I felt drawn to a vocation in health care.

Laura: Through volunteering at community organizations growing up, I became aware of differences in wealth, educational opportunities, and neighborhood resources between Omaha communities. During a college course in Ecuador which focused on social and political transformations, I gained a broader understanding of the global pervasiveness of inequalities, especially in health. In Minnesota where I attended college, I volunteered at a community health clinic teaching an exercise and nutrition class for Hispanic and Somali women struggling with obesity and diabetes. The hard work, persistence, and camaraderie of these women left me inspired and grateful for their friendship and the privilege to take part in their path to better health, and I felt drawn to a vocation in health care. Independence Day is the

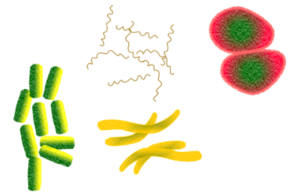

Independence Day is the  Hot Dogs/Deli meat: Staphylococcus aureus – causes nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, cramps within 30 minutes-6 hours

Hot Dogs/Deli meat: Staphylococcus aureus – causes nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, cramps within 30 minutes-6 hours Burgers: Escherichia coli – causes diarrhea, stomach cramps, vomiting within 3-4 days

Burgers: Escherichia coli – causes diarrhea, stomach cramps, vomiting within 3-4 days Step 1 – Clean: Wash your hands, utensils and food handling surfaces often

Step 1 – Clean: Wash your hands, utensils and food handling surfaces often Step 4 – Chill: Refrigerate your food promptly, and at most within 2 hours (within 1 hour if outside temperature is above 90°F). After cooking, put the food back in the cool refrigerator and make sure it can keep temperatures below 40°F. Food left at room temperature for long periods invites bacteria to multiply rapidly, increasing likelihood of foodborne illnesses.

Step 4 – Chill: Refrigerate your food promptly, and at most within 2 hours (within 1 hour if outside temperature is above 90°F). After cooking, put the food back in the cool refrigerator and make sure it can keep temperatures below 40°F. Food left at room temperature for long periods invites bacteria to multiply rapidly, increasing likelihood of foodborne illnesses. Most importantly, WASH YOUR HANDS before and after handling raw meat, before handling non-meat items, and before you sit down to enjoy the fruit of your grilling prowess. (Or at least use hand sanitizer!)

Most importantly, WASH YOUR HANDS before and after handling raw meat, before handling non-meat items, and before you sit down to enjoy the fruit of your grilling prowess. (Or at least use hand sanitizer!)

Recent Comments