Fever has plagued mankind through the ages although was not until the 1600s when Thomas Sydenham reportedly first recognized that fever was an innate response” to get rid of the injurious agents causing the disease”.

In the intensive care unit, fever is one of the most common abnormal signs documented and frequently results in changes in clinical management of the patient, yet we continue to lack adequate evidence regarding the definitions of fever, the incidence, the impact of fever on mortality and whether or not we should treat fever (and if we should, in who).

With this in mind, clinicians need to review fever and the continual evolution of literature regarding this, particularly as it is very likely that temperature management will continue to garner attention regarding how temperature impacts sepsis management and outcomes.

Definition and Pathophysiology

Normothermia: Defined as a normal body temperature of approximately 37.0 C although there is noted variation that is normal of+/- 0.5C throughout the day.

- Fever: There has been a range of temperatures defined as fever in the literature, however a core body temperature of > 38.3 C has been accepted as fever among the critically ill. However, it should be noted that lower temperatures may represent fever in the immunocompromised.

- High Fever: Generally this is defined as a persistent body temperature greater than 39-40 C, although here again there has been some variations in the literature.

- Prolonged Fever: If the duration of fever is >5 days, it is often considered a prolonged fever.

- Hyperthermia: An elevated body temperature, often >41 C, that may be indistinguishable from “fever” clinically, but is due to lack of change in the hypothalamic “setpoint” (See below for further detail).

Pathophysiology

Fever and hyperthermia are notably different mechanisms of alterations in body temperature, although initially these may be difficult to differentiate during a patient evaluation. Thermoregulation is controlled by the hypothalamus, and in fever from infectious and noninfectious causes, the “set point” of temperature by the hypothalamus is increased thereby “allowing” fever. This however is not the case in hyperthermia syndromes. In hyperthermia, there is no change in the hypothalamic “set point” and body temperature is dysregulated resulting in decreased ability for natural heat dissipation.

Measurement of Fever

Measurement of Fever

With the definition of fever behind us, we can focus on how exactly we detect fever. The gold standard for measuring temperature is through a pulmonary artery catheter. However, in the absence of this, we resort to alternative measurements such as thermistors on bladder catheters, esophageal probes or rectal probes. Alternative options also include tympanic membrane or temporal artery thermometers. Of these, rectal, esophageal, bladder and tympanic membrane (not infrared) may be the closest to core body temperature. Axillary, oral and skin temperatures are available but may be impractical and/or less reliable.

Incidence of Fever

Body temperature measurements are ubiquitous in the hospital and intensive care units. Fever is also incredibly common with reports of approximately 25 to greater than 80% of ICU admissions having at least one fever during their ICU stay, and of this approximately 50% are ultimately attributed to infection.

Causes of Fever: Infectious vs Noninfectious vs Hyperthermia

There are many potential causes of fever in the ICU. When evaluating patients, history can be critical to determining if there is a risk for a hyperthermia syndrome such as heat stroke, malignant hyperthermia, neuroleptic malignant syndrome or serotonin syndrome or endocrine diseases causing hyperthermia such as drug intoxication and withdrawal,thyrotoxicosis, adrenal crisis and pheochromocytoma.

Infectious causes a fever are incredibly diverse and may be secondary to a variety of pathogens including bacteria, viruses, protozoa and fungi. Further, some of these fevers will be driven by infections that were present are incubating on arrival to the ICU and others will develop during the ICU stay as a nosocomial infection.

Finally, there are also many noninfectious causes of fever among critically ill. These can include post-operative fevers, drug reactions, thrombosis and emboli or infarct, hemorrhage, pancreatitis, transfusion reactions, pancreatitis or acalculus cholecystitis and occult malignancy among many other potentials.

Given the robust array of potential causes of fever or hypothermia in the critically ill population, providers need to be very thoughtful and thorough when obtaining the initial history, past medical history, review of systems, medications, social and exposures/travel history combined with a thorough examination of the patient to search for potential clues for the cause of fever. Guidelines call for thoughtful evaluation and not to proceed with a reflex fever evaluation.

Managing Fever

Finding fevers, or other abnormal temperatures, among critically ill patient’s is clearly common and impacts clinical decision making however we still lack evidence on whether or not we should intervene on all fevers. The difficulty remains the complex balance between risks and benefits that fever portends to the patient.

The risks and benefit of fever are complex at best. There is always concern for patient discomfort with fever the combined with increased metabolic and oxygen demands raising increased risk of brain damage and multi organ failure. On the other hand, fever is a normal and adaptive response to infection that prompts further evaluation and management from clinicians. Further, this normal febrile response to infection may improve host immune responses, impede bacterial growth, enhance both antimicrobial concentrations and efficacy.

There is ongoing discrepancies in the literature regarding whether or not fever carries increased mortality or not and these variations may be due to timing of fever, severity of fever and underlying comorbidities at the time of fever. In a 2017 meta-analysis, Rombus et al aimed to assess the association between body temperature and mortality among patients with sepsis(10). In this particular study, fever(greater than 38 C) was associated with decreased mortality while hypothermia (<36 C) had a higher associated mortality compared to normothermia. This is concordant with a 2017 study in Critical Care Medicine regarding the predictive value of fever in the emergency department for patients, which demonstrated an inverse relationship between decreased mortality and shorter hospital length of stay associated with higher temperatures on presentation. However, patients with high and prolonged fever have been shown to have higher mortality in some studies.

Treatment of fever in patients with neurologic injury, myocardial ischemia and arguably in severe hypoxia, may improve outcomes, but this does not necessarily translate to all critically ill populations. In addition, hyperthermia syndromes do require emergent therapy which may include stopping the offending agent, antidote and supportive cares including physical cooling. In hyperthermia, antipyretics are not routinely recommended as they are not usually effective in states without an elevated hypothalamic setpoint.

Use of Antipyretics or cooling therapies

Use of Antipyretics or cooling therapies

Finding fever is one thing and deciding to treat it in order to decrease it is another. This area remains one of “hot” debate including whether fever is simply a marker for poorer outcomes or whether active treatment of abnormal body temperature can improve outcomes.

Given the frequency of acetaminophen administration among critically ill patients with fever, a randomized controlled trial assessed treatment versus placebo and did not find a significant difference in the number of ICU free days or 90 day mortality(12). Systematic reviewed meta-analysis of antipyretic therapy among critically ill septic patients also did not demonstrate a significant improvement in 28 day or hospital mortality(6). However, on the contrary, there has been associations of fever with increased mortality prompting further observational study on the association of body temperature and antipyretics treatments with mortality(13). In this study it was noted that in patients without sepsis, high fever (>39.5) was associated with mortality and antipyretics among septic patients increased mortality, raising question into the potential different impacts fever and antipyretics may have depending on whether the patient has sepsis(13). A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of antipyretic use in critically ill adults with sepsis did not find a significant improvement in either 28-day or hospital mortality(6).

Physical cooling therapies are also utilized in both fever and hyperthermia. There is a vast array of technology from the simplicity of ice packs and stands to advanced cooling blankets to intravascular cooling devices. It is unknown if there is a significant difference with these varying methods for cooling patient’s and despite the increased speed and stability of intravascular cooling, we lack substantial evidence to state that this is provides significant improvement in patient outcome(4, 5). All cooling methods carry some risk however the intravascular devices are by nature invasive in carry the risk of central line placement with them(4).

Summary

What to do with abnormal body temperatures, particularly fever, remain an area where we need more research to guide our clinical practice. For now, abnormal temperatures should be evaluated for the underlying etiology and then the art of medicine kicks in – which temperature is right for your patient? Hot, cold or somewhere in between? The many risks and benefits will need to be weighed for each individual patient – unless you have high fever with a hyperthermia syndrome, neurologic injury, myocardial ischemia or severe hypoxia – in these settings, normothermia may prevent further organ damage.

Content by Dr. Kelly Cawcutt.

- Bryan CS. Fever, famine, and war: William Osler as an infectious diseases specialist. Clinical infectious diseases. 1996;23(5):1139-49.

- Laupland KB, Shahpori R, Kirkpatrick AW, Ross T, Gregson DB, Stelfox HT. Occurrence and outcome of fever in critically ill adults. Critical care medicine. 2008;36(5):1531-5.

- Laupland KB. Fever in the critically ill medical patient. Critical care medicine. 2009;37(7):S273-S8.

- Golding R, Taylor D, Gardner H, Wilkinson JN. Targeted temperature management in intensive care–Do we let nature take its course? Journal of the Intensive Care Society. 2016;17(2):154-9.

- Kushimoto S, Yamanouchi S, Endo T, Sato T, Nomura R, Fujita M, et al. Body temperature abnormalities in non-neurological critically ill patients: a review of the literature. Journal of Intensive Care. 2014;2(1):14.

- Drewry AM, Ablordeppey EA, Murray ET, Stoll CR, Izadi SR, Dalton CM, et al. Antipyretic Therapy in Critically Ill Septic Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Critical care medicine. 2017;45(5):806.

- Rehman T. Persistent fever in the ICU. CHEST Journal. 2014;145(1):158-65.

- O’Grady NP, Barie PS, Bartlett JG, Bleck T, Carroll K, Kalil AC, et al. Guidelines for evaluation of new fever in critically ill adult patients: 2008 update from the American College of Critical Care Medicine and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Critical care medicine. 2008;36(4):1330-49.

- Niven DJ, Laupland KB. Pyrexia: aetiology in the ICU. Critical Care. 2016;20(1):247.

- Rumbus Z, Matics R, Hegyi P, Zsiboras C, Szabo I, Illes A, et al. Fever Is Associated with Reduced, Hypothermia with Increased Mortality in Septic Patients: A Meta-Analysis of Clinical Trials. PloS one. 2017;12(1):e0170152.

- Sundén-Cullberg J, Rylance R, Svefors J, Norrby-Teglund A, Björk J, Inghammar M. Fever in the Emergency Department Predicts Survival of Patients With Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock Admitted to the ICU. Critical care medicine. 2017;45(4):591-9.

- Patel J. Acetaminophen for Fever in Critically Ill Patients with Suspected Infection. The New England journal of medicine. 2016;374(13):1291.

- Lee BH, Inui D, Suh GY, Kim JY, Kwon JY, Park J, et al. Association of body temperature and antipyretic treatments with mortality of critically ill patients with and without sepsis: multi-centered prospective observational study. Critical care. 2012;16(1):R33.

Measurement of Fever

Measurement of Fever

Use of Antipyretics or cooling therapies

Use of Antipyretics or cooling therapies A delay in the administration of effective antimicrobial therapy can lead to significantly increased mortality [4]. Due to the rapid progression to life-threatening organ dysfunction or death, antimicrobials are liberally administered in all suspected cases of sepsis. Unfortunately, this practice may contribute to the development of antimicrobial resistance. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimate

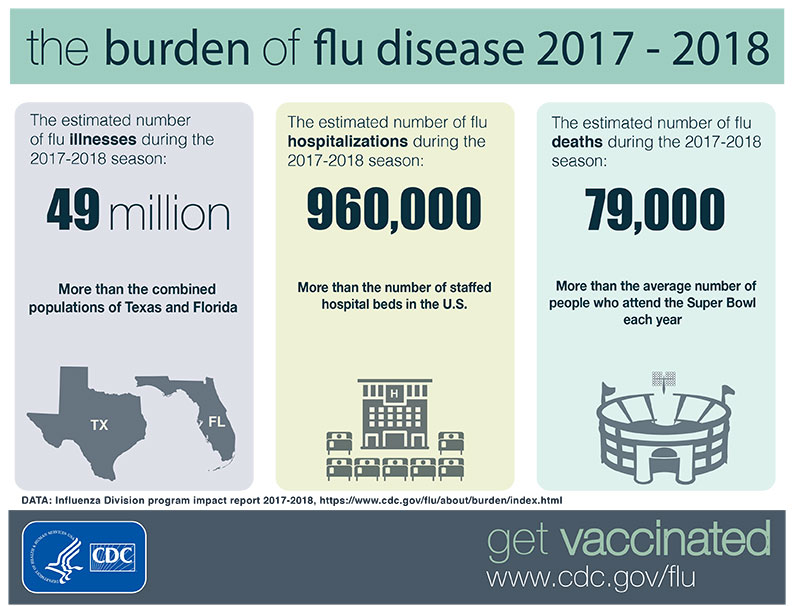

A delay in the administration of effective antimicrobial therapy can lead to significantly increased mortality [4]. Due to the rapid progression to life-threatening organ dysfunction or death, antimicrobials are liberally administered in all suspected cases of sepsis. Unfortunately, this practice may contribute to the development of antimicrobial resistance. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimate  Although this study showed SeptiCyte could accurately differentiate between infectious and non-infectious causes of SIRS, the assay has several weaknesses. First, the SeptiCyte assay took 6 hours to result, so it would likely not be more useful in sepsis identification than some newer and emerging rapid diagnostic tests; therefore the cost-effectiveness to clinical utility balance is yet to be determined. Additionally, the study included patients with SIRS and only included patients already in the ICU, when the emergency department may be the first point of initiation of any institutional sepsis protocol. Finally, the test performance was lowest with pneumonia, which is one of the the most common causes of sepsis in the ICU, again questioning the clinical utility. Other questions remain such as whether this technology would have a role in out-of-hospital sepsis bundle initiation.

Although this study showed SeptiCyte could accurately differentiate between infectious and non-infectious causes of SIRS, the assay has several weaknesses. First, the SeptiCyte assay took 6 hours to result, so it would likely not be more useful in sepsis identification than some newer and emerging rapid diagnostic tests; therefore the cost-effectiveness to clinical utility balance is yet to be determined. Additionally, the study included patients with SIRS and only included patients already in the ICU, when the emergency department may be the first point of initiation of any institutional sepsis protocol. Finally, the test performance was lowest with pneumonia, which is one of the the most common causes of sepsis in the ICU, again questioning the clinical utility. Other questions remain such as whether this technology would have a role in out-of-hospital sepsis bundle initiation.

Since 2009’s pandemic, seasonal influenza is still prevalent, with an estimate of over

Since 2009’s pandemic, seasonal influenza is still prevalent, with an estimate of over  What it is

What it is How we can prevent it

How we can prevent it

Recent Comments