Antibiotic Awareness Week 2021,”an annual observance that raises awareness of the threat of antibiotic resistance and the importance of appropriate antibiotic use” runs this year from November 18-24 2021. This is a global campaign with messaging from the CDC and the WHO calling on all of us to not only Be Antibiotics Aware, but to actively engage in activities to reduce the spread of antimicrobial resistance.

To kick off #USAAW21 and #WAAW21, we share this #ThrowbackThursday publication from September 2020: Confronting antimicrobial resistance beyond the COVID-19 pandemic and the 2020 US election. I coauthored this perspective in the Lancet with Drs. Steffanie Strathdee and Sally Davies.

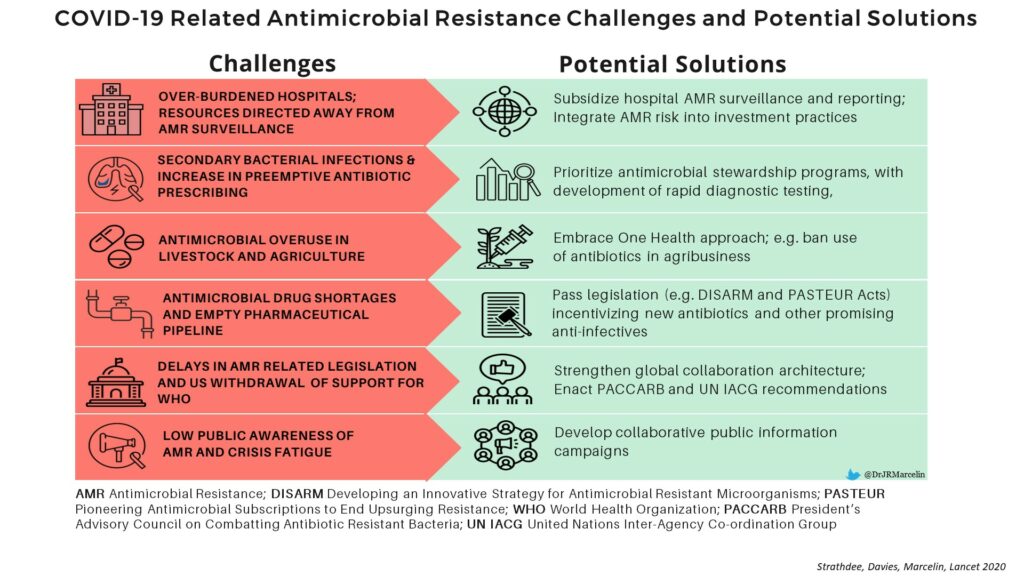

In this article, we highlighted ongoing challenges due to antimicrobial resistance worldwide: 700K deaths per year, costing US100 trillion globally, and more than 2.8 million infections/35K deaths/$20billion in healthcare expenditures in the US.

We also described how the current COVID-19 pandemic is likely exacerbating antimicrobial resistance, with excessive antibiotic use when not clinically indicated, and redirection of resources globally away from antimicrobial stewardship to COVID-19 activities.

We end with a call to action that “the path forward is not only one that builds back from the COVID-19 pandemic, but also addresses AMR in the context of pandemic preparedness” and “collaboration is the most effective way to tackle global health threats“.

Read more of the perspective piece here: https://www.thelancet.com/article/S0140-6736(20)32063-8/fulltext/#bib2

Recent Comments