IDWeek is here and we want to be sure YOU know where to find us! Below is the list of faculty presentations and posters from our Division. Please come visit us at IDWeek – We would LOVE to meet you!

Content courtesy of Sandy Nelson and the entire UNMC ID Division.

Tuesday, October 2

Session: The Vincent T. Andriole ID Board Review Course

Session Title: Infections in Transplant

Presenter: Andrea Zimmer, MD

Session time: 8:00 a.m. – 5:00 p.m.

Session location: W 2005-2020

Thursday October 4

Meet-the-Professor Session

Session: Are You Ready? Outbreak Response Training

Presenter: Angela Hewlett, MD

Session time: 7:15-8:15 a.m.

Session location: S 152-154

Session: Cool Findings in Bacteremia and Endocarditis

Session Time: 11:30-12:45 p.m.

Session Location: W 2002

Presentation Title: The Effect of Insurance Coverage on Appropriate Selection of Hospital Discharge Antibiotics for Staphylococcus aureus Bacteremia

Authors: Mark E. Rupp, MD, Trevor Van Schooneveld, MD, FACP et al

Presentation Number: 158

Posters 12:30-1:45pm

Session: Antimicrobial Stewardship: Interventions Leveraging the Electronic Health Record

Presentation Title: Impact of a Best Practice Alert Linking Clostridium difficile Infection Test Results to a Severity-based Treatment Order Set

Authors: Trevor Van Schooneveld, MD, FACP, Scott Bergman, PharmD, FIDSA, FCCP, BCPS et al

Presentation Number: 178

Session: Antimicrobial Stewardship: Interventions to Improve Outcomes

Presentation Title: Respiratory Viral Testing is Associated with Lower Frequency of Antibiotic Prescribing for Acute Upper Respiratory Infections at a Large Ambulatory Cancer Center

Authors: Erica Stohs, MD, MPH et al

Presentation Number: 206

Session: Bone and joint Infections

Presentation Title: Effect of Previous Antibiotic Exposure on the Yield of Bone Biopsy Culture in Patients with Osteomyelitis

Authors: Paul Fey PhD, Angela Hewlett MD, Mark Rupp MD et al

Presentation Number: 291

Session: Fungal Disease: Management and Outcomes

Presentation Title: Breakthrough Pneumocystis jirovecii Pneumonia among Cancer Patients: Opportunity for Antimicrobial Stewardship?

Authors: Erica Stohs, MD, MPH et al

Presentation Number: 402

Session: Microbiome and Beyond

Presentation Title: Vancomycin is Frequently Administered to Hematopoietic Cell Transplant Recipients without a Provider Documented Indication and Correlates with Microbiome Disruption and Adverse Events.

Authors: Erica Stohs, MD et al

Presentation Number: 616

Friday, October 5

Posters 12:30-1:45pm

Session: Bacteremia and Endocarditis

Presentation Title: Bloodstream Infection Survey in High-Risk Oncology Patients (BISHOP) with Fever AND Neutropenia (FN): Predictors for Morbidity and Mortality

Authors: Alison G. Freifeld, MD, Andrea Zimmer, MD, et al

Presentation Number: 1016

Session: Diarrhea Diagnostic Dilemmas

Presentation Title: The Value of Hardwiring Diagnostic Stewardship in the Electronic Health Record: Electronic Ordering Restrictions for PCR-Based Rapid Diagnostic Testing of Diarrheal Illnesses

Authors: Jasmine R Marcelin MD, Caitlin N. Murphy PhD, Paul D. Fey PhD, Trevor C. Van Schooneveld MD (et. al)

Presentation Number: 1095

Session: Healthcare Epidemiology: Non-acute Care Settings

Presentation Title: Infection Control Risk Mitigation and Implementation of Best Practice Recommendations in Long-term Care Facilities

Authors: Mark E. Rupp, MD, Muhammad Salman Ashraf, MBBS et al

Presentation Number: 1236

Session: Healthcare Epidemiology: Non-acute Care Settings

Presentation Title: Frequently Identified Infection Control Gaps in Outpatient Hemodialysis Centers

Authors: Mark E. Rupp, MD, Muhammad Salman Ashraf, MBBS et al

Presentation Number: 1239

Session: HIV: Diagnosis and Screening

Presentation Title: Routine opt-out HIV screening and detection of HIV infection among emergency department patients

Authors: Nada Fadul, MD et al

Presentation Number: 1273

Session: HIV: Prevention

Presentation Title: Knowledge, Attitudes and Barriers of Pre-exposure Prophylaxis for HIV Infection Among Resident Physicians in Rural, Eastern North Carolina

Authors: Nada Fadul, MD et al

Presentation Number: 1289

Session: HIV: Prevention

Presentation Title: Acceptability and Feasibility of a Pharmacist-led Pre-exposure Prophylaxis Program in the Midwestern United States

Authors: Sara H. Bares, Joshua P. Havens, Kimberly K. Scarsi, Susan Swindells et al

Presentation Number: 1294

Session: Medical Education

Presentation Title: Antibiotic Prescribing Knowledge: A Brief Survey of Providers and Staff at an Ambulatory Cancer Center during Antibiotic Awareness Week 2017

Authors: Erica Stohs, MD, MPH et al

Presentation Number: 1302

Session: Respiratory Infections: Miscellaneous

Presentation Title: Impact of a Guidance Document, Order Set Changes and Physician Education on Antibiotic Prescribing in Acute Exacerbation of COPD

Authors: Scott Bergman, Trevor Van Schooneveld et al

Presentation Number: 1480

Session:Viruses and Bacteria in Immunocompromised Patients

Presentation Title: Bloodstream Infection Survey in High-Risk Oncology Patients (BISHOP) with Fever AND Neutropenia (FN): Correlation between Initial Empiric Antibiotic Regimen Correlation and Susceptibility Patterns

Authors: Andrea Zimmer, MD, Alison G. Freifeld, MD et al

Presentation Number: 1585

Saturday October 6

Session: Febrile Neutropenia

Session Title: Infections in Immunocompromised Hosts

Presenter: Alison Freifeld, MD

Session time: 10:30-11:45 a.m.

Session location: S 214-216

Posters 12:30-1:45 p.m.

Session: HIV: Sexually Transmitted Infections

Presentation Title: Assessment of Anal Papanicolaou Smear Screening and Follow-up Rates in Eastern North Carolina for HIV-Positive Patients who are Men who have Sex with Men

Authors: Nada Fadul, MD et al

Presentation Number: 2274

Session: Antimicrobial Stewardship: Non-hospital Settings

Presentation Title: Comparison of Antibiotic Use in Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Facilities Based on Proportion of Short Stay Residents Using a Long-Term Care Pharmacy Database

Authors: Philip Chung, PharmD, MS, BCPS, Scott Bergman, PharmD, FIDSA, FCCP, BCPS, Mark E. Rupp, MD, Trevor Vanschooneveld, MD, Muhammad Salman Ashraf, MBBS et al

Presentation Number: 1837

Session: Antimicrobial Stewardship: Non-hospital Settings

Presentation Title: Digging Deeper: A Closer Look at Core Elements of Antibiotic Stewardship for Long-Term Care Facilities

Authors: Scott Bergman, PharmD, FIDSA, FCCP, BCPS, Philip Chung, PharmD, MS, BCPS, Mark E. Rupp, MD, Trevor Vanschooneveld, MD, Muhammad Salman Ashraf, MBBS et al

Presentation Number: 1838

Session: 222. Antimicrobial Stewardship: Potpourri

Presentation Title: Adherence to Practice Guidelines for Treating Diabetic Foot

Infections: An Opportunity for Syndromic Stewardship

Authors: McCreery R, Bergman SJ, Van Schooneveld TC

Presentation Number: 1874

Session: Healthcare Epidemiology: Device-associated HAIs

Presentation Title: Evaluation of a Midline Catheter Program and Effect on Central Line Associated Blood Stream Infections

Authors: Richard Hankins, MD; Mark Rupp, MD, Kelly Cawcutt, MD, MS et al

Presentation Number: 2096

Find us on Twitter @UNMC_ID; #UNMCID #IDWEEK2018

ID Pharmacist Scott Bergman (@bergmanscott) and our ID faculty #tweeterIDians Drs. Jasmine Marcelin (@DrJRMarcelin), Kelly Cawcutt (@KellyCawcuttMD), Nada Fadul (@fadul_nada), Salman Ashraf (@M_Salman_Ashraf), Erica Stohs @EStohs will be tweeting from the conference, so join us in the conversation!

The dogs had a moderate interrater reliability with a Cohen’s kappa of 0.52. Both dogs had about 85% specificity of toxigenic C. difficile detection but the German Shepherd’s sensitivity of detection out-sniffed the Border Collie Pointer (92% vs 78% respectively). Positive predictive value for both dogs was <50% and negative predictive value was >95% for both dogs. Interrater variability necessitates individualized dog training; and it is curious that two different species were used – could there be a genetic predisposition for “better” olfactory receptors in certain species?

The dogs had a moderate interrater reliability with a Cohen’s kappa of 0.52. Both dogs had about 85% specificity of toxigenic C. difficile detection but the German Shepherd’s sensitivity of detection out-sniffed the Border Collie Pointer (92% vs 78% respectively). Positive predictive value for both dogs was <50% and negative predictive value was >95% for both dogs. Interrater variability necessitates individualized dog training; and it is curious that two different species were used – could there be a genetic predisposition for “better” olfactory receptors in certain species? Trained Giant African pouched rats can accurately sniff tuberculosis in Tanzania, and dogs have been trained to detect drugs and explosives for law enforcement, so why not C. difficile?Though the concept is exciting, this is miles away from mainstreaming due to effort and lack of generalizability.

Trained Giant African pouched rats can accurately sniff tuberculosis in Tanzania, and dogs have been trained to detect drugs and explosives for law enforcement, so why not C. difficile?Though the concept is exciting, this is miles away from mainstreaming due to effort and lack of generalizability. If two different canine species could not agree on whether or not the stool smelled “diffy”, where does that leave humans, whose olfactory capabilities are thought to be 10,000- to 100,000-fold less sensitive than dogs? Perhaps when it comes to C. difficile, no nose knows better than conventional testing.

If two different canine species could not agree on whether or not the stool smelled “diffy”, where does that leave humans, whose olfactory capabilities are thought to be 10,000- to 100,000-fold less sensitive than dogs? Perhaps when it comes to C. difficile, no nose knows better than conventional testing.

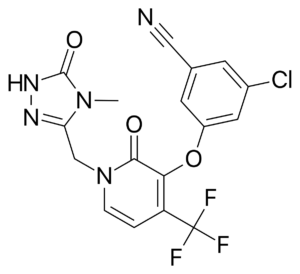

Doravirine (DOR) is a novel NNRTI that provides a similar efficacy for the treatment of HIV infection with activity against HIV variants that are resistant to efavirenz (EFV) and rilpivirine (RPV). Doravirine offers a better safety profile without neuropsychiatric adverse effects, minimal drug-drug interactions and is unaffected by food intake and need for an acidic absorption environment. In August, 2018, doravirine was approved by the FDA for use and will be available solely (Pifeltro™) or as a single tablet regimen (Delstrigo™) in combination with lamivudine (3TC) and tenofovir disoproxil fumurate (TDF).

Doravirine (DOR) is a novel NNRTI that provides a similar efficacy for the treatment of HIV infection with activity against HIV variants that are resistant to efavirenz (EFV) and rilpivirine (RPV). Doravirine offers a better safety profile without neuropsychiatric adverse effects, minimal drug-drug interactions and is unaffected by food intake and need for an acidic absorption environment. In August, 2018, doravirine was approved by the FDA for use and will be available solely (Pifeltro™) or as a single tablet regimen (Delstrigo™) in combination with lamivudine (3TC) and tenofovir disoproxil fumurate (TDF). DRIVE-AHEAD2: A randomized, double-blind, phase III trial compared doravirine to another NNRTI, efavirenz. Adults with HIV-1 infection naïve to ART, HIV RNA >1,000 copies/ml, and CD4 >100/mm3 were randomized to receive DOR 100mg with 3TC 300mg/TDF 300mg or EFV 600mg with TDF 300mg/emtricitabine (FTC) 200mg. The primary endpoint of the study measured virologic response with the proportion of patients achieving HIV RNA <40 copies/ml at week 48. Comparisons between each arm were similar, 77% in DOR arm vs. 78% in EFV arm, demonstrating non-inferiority. Clinical adverse events deemed drug-related were reported in 31% of patients in DOR arm and 56% in EFV arm. Dizziness (6.5% DOR vs. 25% EFV) and abnormal dreams (5.6% DOR vs. 14.8% EFV) had the largest variation between the two groups. Only one emergent NNRTI mutation arose to the DOR group, K101K/E mutation, which causes intermediate resistance to RPV and low-level resistance to EFV.

DRIVE-AHEAD2: A randomized, double-blind, phase III trial compared doravirine to another NNRTI, efavirenz. Adults with HIV-1 infection naïve to ART, HIV RNA >1,000 copies/ml, and CD4 >100/mm3 were randomized to receive DOR 100mg with 3TC 300mg/TDF 300mg or EFV 600mg with TDF 300mg/emtricitabine (FTC) 200mg. The primary endpoint of the study measured virologic response with the proportion of patients achieving HIV RNA <40 copies/ml at week 48. Comparisons between each arm were similar, 77% in DOR arm vs. 78% in EFV arm, demonstrating non-inferiority. Clinical adverse events deemed drug-related were reported in 31% of patients in DOR arm and 56% in EFV arm. Dizziness (6.5% DOR vs. 25% EFV) and abnormal dreams (5.6% DOR vs. 14.8% EFV) had the largest variation between the two groups. Only one emergent NNRTI mutation arose to the DOR group, K101K/E mutation, which causes intermediate resistance to RPV and low-level resistance to EFV. DRIVE-FORWARD3: A randomized, controlled, double-blind, phase III, non-inferiority trial compared doravirine to ritonavir-boosted darunavir, a protease inhibitor. Adults with HIV-1 infection naïve to ART, with plasma HIV RNA >1,000 copies/ml were screened and randomized to receive DOR 100mg or DRV 800mg/RTV 100mg (DRV/r), in combination with either TDF/FTC or ABC/3TC based on investigator choice. The proportion of patients that achieved plasma HIV-1 RNA <50 copies/ml at week 48 defined the primary endpoint of this trial. Doravirine showed non-inferiority to ritonavir boosted darunavir, with 84% in DOR arm vs. 80% in DRV/r arm achieving success with HIV RNA <50c/ml at week 48. Clinical adverse events due to drug therapy were reported in 31% in DOR and 32% in DRV/r group, with diarrhea comprising 5% of DOR patients vs. 13% of DRV/r patients. Lab abnormalities were similar between the two regimens, except LDL-cholesterol increases in <1% of DOR patients vs. 9% of DRV/r patients. Resistance testing was performed in 15 protocol-defined virologic failure (PDVF) patients, and within this group no emergent mutations to DOR were found. One case of resistance was found in a patient that discontinued treatment because of non-compliance at week 24, thus was not included in the PDVF category, encompassing resistance to DOR (V106I, H221Y, F227C) and FTC (M184V).

DRIVE-FORWARD3: A randomized, controlled, double-blind, phase III, non-inferiority trial compared doravirine to ritonavir-boosted darunavir, a protease inhibitor. Adults with HIV-1 infection naïve to ART, with plasma HIV RNA >1,000 copies/ml were screened and randomized to receive DOR 100mg or DRV 800mg/RTV 100mg (DRV/r), in combination with either TDF/FTC or ABC/3TC based on investigator choice. The proportion of patients that achieved plasma HIV-1 RNA <50 copies/ml at week 48 defined the primary endpoint of this trial. Doravirine showed non-inferiority to ritonavir boosted darunavir, with 84% in DOR arm vs. 80% in DRV/r arm achieving success with HIV RNA <50c/ml at week 48. Clinical adverse events due to drug therapy were reported in 31% in DOR and 32% in DRV/r group, with diarrhea comprising 5% of DOR patients vs. 13% of DRV/r patients. Lab abnormalities were similar between the two regimens, except LDL-cholesterol increases in <1% of DOR patients vs. 9% of DRV/r patients. Resistance testing was performed in 15 protocol-defined virologic failure (PDVF) patients, and within this group no emergent mutations to DOR were found. One case of resistance was found in a patient that discontinued treatment because of non-compliance at week 24, thus was not included in the PDVF category, encompassing resistance to DOR (V106I, H221Y, F227C) and FTC (M184V).

In the second article, “

In the second article, “

Under the coaching of Vintage Ballroom instructor, Rebekah Pasqualetto, three pediatric patients are teaming up with the doctors’ who saved them to put on the biggest performance of their young lives. The dancing isn’t easy. Between school, doctor appointments, and daily lives the girls dedicated two months to learning three styles of dance: Rumba, Merengue, and Country Swing. Each song matches the personality of each child. 11-year old Daisy likes to dance with her friends to the latest pop hits. 12-year old Maura has dance training from previous years of ballet. Even with surgery restrictions, Maura is adamant about performing a trick on the dance floor. 12-year old Raeleigh loves fashion, she is very considerate of others. Raeleigh will be joined on the dance floor by her younger sister Addisyn who suffers from watching Raeleigh undergo treatment.

Under the coaching of Vintage Ballroom instructor, Rebekah Pasqualetto, three pediatric patients are teaming up with the doctors’ who saved them to put on the biggest performance of their young lives. The dancing isn’t easy. Between school, doctor appointments, and daily lives the girls dedicated two months to learning three styles of dance: Rumba, Merengue, and Country Swing. Each song matches the personality of each child. 11-year old Daisy likes to dance with her friends to the latest pop hits. 12-year old Maura has dance training from previous years of ballet. Even with surgery restrictions, Maura is adamant about performing a trick on the dance floor. 12-year old Raeleigh loves fashion, she is very considerate of others. Raeleigh will be joined on the dance floor by her younger sister Addisyn who suffers from watching Raeleigh undergo treatment. Dr. Diana Florescu is coordinating the fundraiser with Child Life, Vintage Ballroom, and Nebraska Dance Festival. The organizers of Nebraska Dance Festival – Amanda & Ilya Reyzin and Igor Litvinov – are supporting Child Life Services from University of Nebraska Medical Center! Through their donation, they will share the gift of reading and spread some fun to pediatric patients at Nebraska Medicine. Hospitalization can be a scary and isolating experience for children and teens. Many of the kids are hospitalized for long periods of time – months or even years – due to the severity of their illnesses. Books and games will allow kids to experience normalcy, socialization, and continued growth and development while hospitalized.

Dr. Diana Florescu is coordinating the fundraiser with Child Life, Vintage Ballroom, and Nebraska Dance Festival. The organizers of Nebraska Dance Festival – Amanda & Ilya Reyzin and Igor Litvinov – are supporting Child Life Services from University of Nebraska Medical Center! Through their donation, they will share the gift of reading and spread some fun to pediatric patients at Nebraska Medicine. Hospitalization can be a scary and isolating experience for children and teens. Many of the kids are hospitalized for long periods of time – months or even years – due to the severity of their illnesses. Books and games will allow kids to experience normalcy, socialization, and continued growth and development while hospitalized.

During the month rotation a small special project is also conducted and a specialized curriculum/lecture series is conducted. ID fellows are exposed to the infection control literature during a monthly infection control journal club in which they take turns critiquing recent publications along with IPs and faculty. The infection control experience is capped off by attendance of the SHEA/CDC basic course in Hospital Epidemiology. For the ID fellow interested in infection control as a career, opportunity for a third year of Fellowship directed toward specialized training in infection control and hospital epidemiology is encouraged.

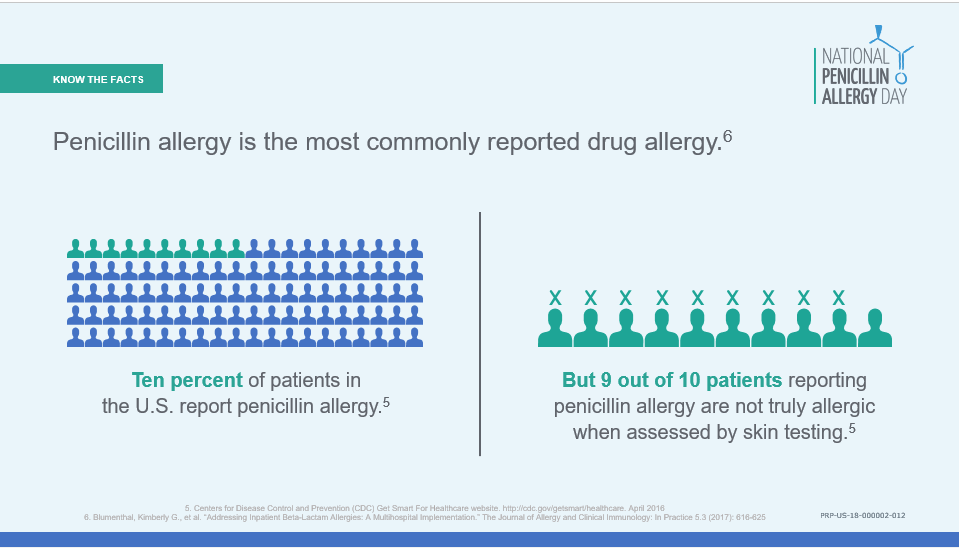

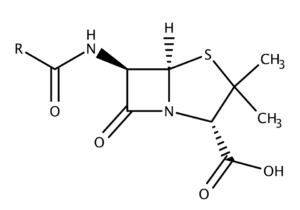

During the month rotation a small special project is also conducted and a specialized curriculum/lecture series is conducted. ID fellows are exposed to the infection control literature during a monthly infection control journal club in which they take turns critiquing recent publications along with IPs and faculty. The infection control experience is capped off by attendance of the SHEA/CDC basic course in Hospital Epidemiology. For the ID fellow interested in infection control as a career, opportunity for a third year of Fellowship directed toward specialized training in infection control and hospital epidemiology is encouraged. Penicillin allergies are

Penicillin allergies are  Once a penicillin allergy is listed in a patient’s record, they are more likely to receive inappropriate broad-spectrum antibiotics – a

Once a penicillin allergy is listed in a patient’s record, they are more likely to receive inappropriate broad-spectrum antibiotics – a  There’s an age-old joke that if a team wants a detailed history on a patient, just consult ID. If our attention to detail is already expected, shouldn’t we feel empowered to take that allergy history and de-label the penicillin allergy? Inpatient allergy consultations are difficult to coordinate when those divisions may be understaffed and allergists are busy with outpatient practices. So how can we capitalize on their expertise when they can’t see the patient in the hospital? Simple: partner with them to create

There’s an age-old joke that if a team wants a detailed history on a patient, just consult ID. If our attention to detail is already expected, shouldn’t we feel empowered to take that allergy history and de-label the penicillin allergy? Inpatient allergy consultations are difficult to coordinate when those divisions may be understaffed and allergists are busy with outpatient practices. So how can we capitalize on their expertise when they can’t see the patient in the hospital? Simple: partner with them to create  In honor of Sir Alexander Fleming and

In honor of Sir Alexander Fleming and

Recent Comments