It is that time of year again, the fresh transition into fall, and for the Infectious Diseases world, the growing excitement for IDWeek. This year, UNMC ID will again be active at throughout the conference.

Where can you find us?

First, follow us on Twitter @UNMC_ID throughout the conference!

Second, we have faculty who will be participating in the mentorship program, so keep your eyes open & please say hello!

Third, there are several presentations from our faculty and fellows, and here is the list of talks! We hope to see you there!

If you missed it, Dr. Andrea Zimmer presented on Thursday, September 23rd on “Transplant Infections”!

Still upcoming presentations from faculty:

- Dr. Susan Swindells will be presenting Thursday, September 30, with her session entitled “Challenging HIV cases” (#32)

- Dr. Trevor Van Schooneveld has several presentations on October 1st, including “Big Beasts of Skin & Soft Tissue Infections” (#95) and “SSTI Imposters”

- Dr. Kelly Cawcutt will be presenting Friday, October 1st in “Competing Priorities Between Antimicrobial Stewardship and Other Hospital Needs”; with her talk entitled “ASP vs IC: Turf War or Battle Buddies?” (#106)

- Dr. Nicolas Cortes will be presenting Friday, October 1 with his presentation entitled “What’s New in Orthopedic Infections: Bone Appetit!” (#102)

- Dr. Angela Hewlett will be presenting on Friday, October 1st with her session entitled “Update on Natural and Prosthetic Vascular Graft Infections” (#101)

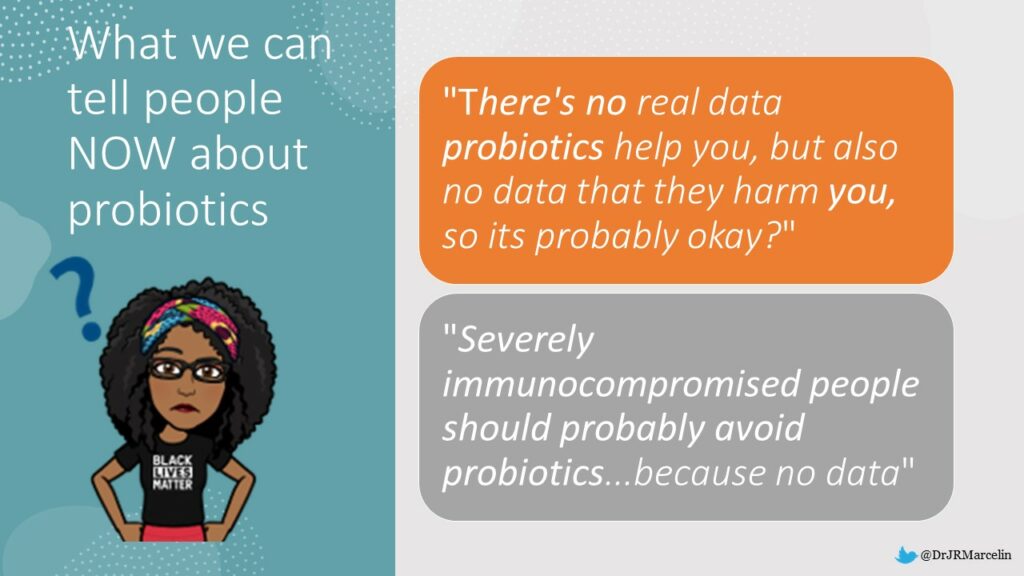

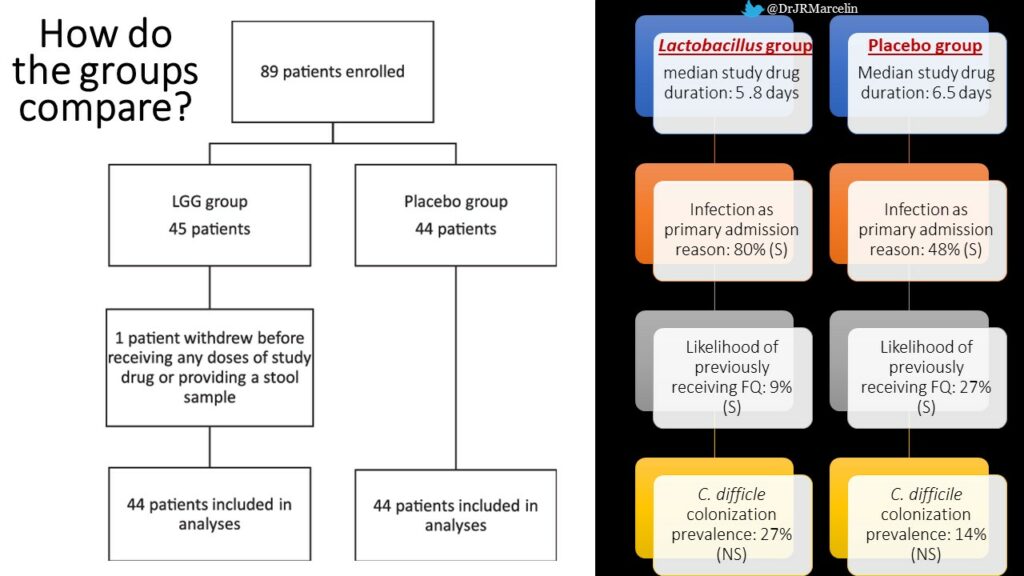

- Dr. Marcelin has several presentations on Friday, October 1st and Saturday October 2nd including “

- Competing Priorities Between Antimicrobial Stewardship and Other Hospital Needs” (#106); “Leadership in the Time of Social Media (#124), and “ID Divisions in the 21st Century” Strategy & Best Practices for Social Media Engagement”

- Dr. Scott Bergman will be presenting Saturday, October 2nd with his presentation entitled ” TDM for Beta-Lactams: Ready for Prime Time?” (#119)

Abstract & Poster Presentations:

- Dr. Jonathan Ryder (UNMC ID Fellow) will be presenting “Is There Value of Infectious Diseases Consultation in Candidemia? A Single Center Retrospective Review from 2016-2019” (#988)

- Dr. Laura Selby (UNMC ID Fellow) will be presenting “Effect of SARs-Cov-2 mRNA Vaccination in Healthcare Workers with Household COVID Exposure” (#421)

- Dr. Sara Bares (UNMC ID faculty) will be presenting “A Multi-faceted, Iterative Program to Increase COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake in a Midwestern HIV Clinic” (#1196)

- Dr. M. Salman Ashraf (UNMC ID faculty) will be presenting “Resources Needed by Critical Access Hospitals to Address Identified Infection Prevention and Control Program Gaps” (#954)

- Dr. Nicolas Cortes-Penfield (UNMC ID faculty) will be presenting “Infection Prevention and Control Training Needs and Preferences Among Frontline Health Professionals” (#797)

- Dr. Andrew B Watkins (UNMC ID Faculty) will be presenting “Implementation and Outcomes of a Program to Coordinate and Administer Monoclonal Antibody Therapy to Long-Term Care Facility Residents with COVID-19” (#501)

- Dr. Nada Fadul and Nichole Regan will be presenting “Telemedicine Implementation at a Midwestern HIV Clinic During COVID-19: One Year Outcomes” (#878)

- Dr. Fadul will be presenting “Factors Associated with Lack of Viral Suppression Among Women Living with HIV in the United States: An Integrative Review.” (#884)

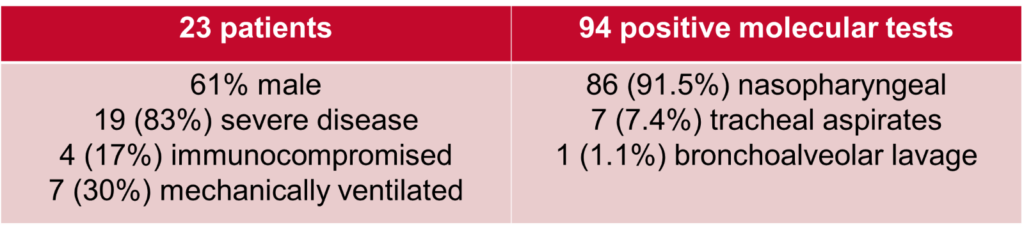

- Dr. Fadul will be presenting “Structural Vulnerability among Patients with HIV and SARS-CoV-2 Coinfection: Descriptive Case Series from the U.S. Midwest” (#464)

undefined

Recent Comments