The SHEA Spring 2025 meeting promises to be a vibrant gathering of thought leaders in healthcare epidemiology and infection prevention. Held from April 26-30, 2025, in beautiful Championsgate, FL, the event will feature groundbreaking research, innovative practices, and insightful discussions. We’re thrilled to highlight the brilliant presenters from our division, each contributing to the advancement of healthcare practices:

Posters:

- Division Authors: Kate Tyner*, Jody Scebold, M. Salman Ashraf, Dan German, Rebecca Martinez, Josette McConville, Sarah Stream, Mounica Soma, Juan Teran Plascencia (Nebraska ICAP)

Presentation: Infection Prevention Program Infrastructure and Implementation of Best Practice Recommendations in Outpatient Healthcare Facilities

Times:- Poster session: Wednesday, April 30, 12:00–1:30 PM

- Featured in a Science Salon: Monday, April 28, 1:00–1:30 PM (presented by a SHEA SME)

- Division Authors: Evangeline (Gigi) Green*, Jonathan Ryder, and Jasmine R. Marcelin

Presentation: Turning Crisis into Opportunity: Blood Culture Stewardship and the National Impact of a Blood Culture Shortage on Clinical Care

Time: Poster Session: Tuesday, April 29, 12:00–1:30 PM - Division Authors: Miranda Neumann*, Monica Krause, Kelly Goetschkes, Lauren Musil, Mark E. Rupp, Kelly A. Cawcutt

Presentation: Knobmanship – A Means to Avoid False Positive Burden of VAE

Time: Poster Session: Wednesday, April 30, 12:00–1:30 PM - Division Authors: Richard Hankins*, Miranda Neumann, Elizabeth Grashorn, Kelly Cawcutt

Presentation: Evaluation of Healthcare-Associated Infections and Daily Bathing Compliance on BMT Unit after Introduction of 2% CHG Wipes

Time: Poster Session: Monday April 28th from 12:00-1:30pm - Division Authors: Jenna Preusker, Juan Teran Placencia, Trevor Van Schooneveld, Scott Bergman, Danny Schroeder, M. Salman Ashraf

Presentation: Analyzing Antibiotic Usage Rates Reported to NHSN by Nebraska Hospitals: Insights by Hospital Size and Rurality

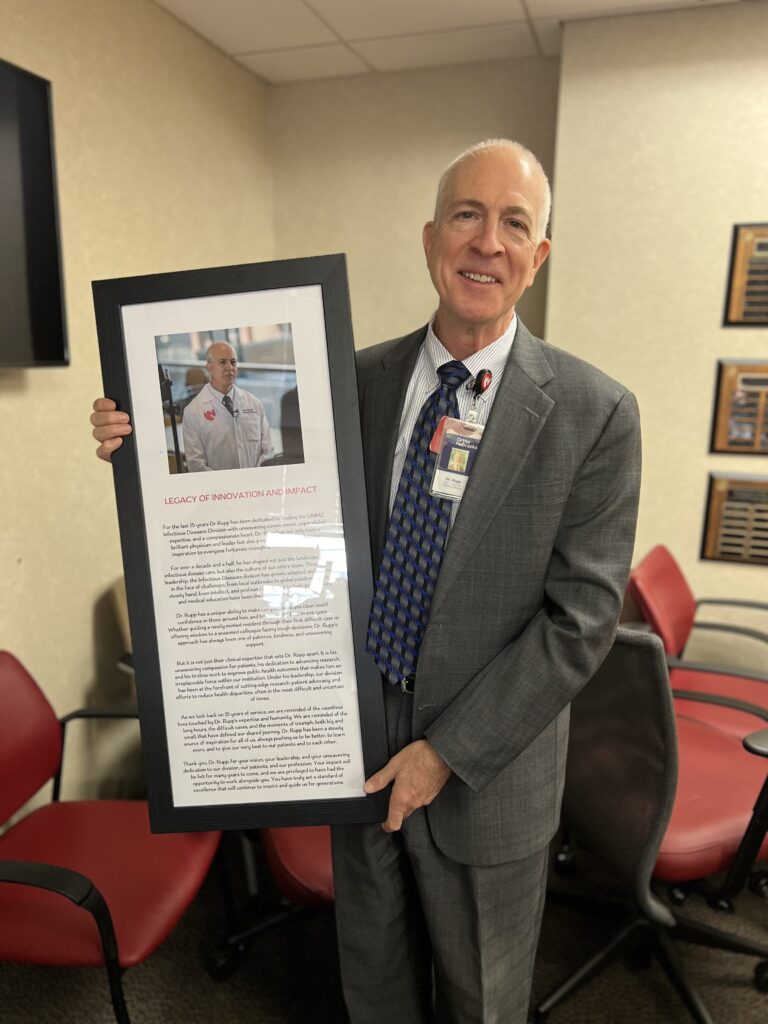

Time: Poster Session: Monday April 28th from 12:00-1:30pm - Division Authors: Mark Rupp

Presentation: Multi-Center, Randomized Study To Evaluate The Efficacy And Safety of Mino-Lok for the management of CLABSI In Hemodialysis Patients

Time: Poster Session: Monday April 28th from 12:00-1:30pm

*Presenting Author

Oral Abstracts

Division Presenters: Jonathan Ryder*, Trevor Van Schooneveld, and Kelly Cawcutt

Presentation: Are SEP-1 and Blood Culture Stewardship at Odds? Retrospective Review of SEP-1 Failures Pre- and During Blood Culture Shortage

Time: Wednesday, April 30, 2025, 8:30–9:30 AM

*Presenting Author

Invited Podium Presentations

Division Speaker: Angela Hewlett

Presentation: Approach to Novel Viral Pathogens with Pandemic Potential

Time: Monday, April 28, 2025, 11:00–11:30 AM

Division Speaker: Jasmine R Marcelin

Presentation: Strategic Stewardship: Essential Skills for Effective Leadership

Time: Wednesday, April 30th, 2025, from 1:30 PM to 2:30 PM.

Division Speaker: M. Salman Ashraf

Presentation: Context: IPC in LTC- where would decolonization fit

Time: Wednesday, April 30th, 2025, from 11:33AM to 11:48AM

Panel Speakers

Division Speaker: M. Salman Ashraf

Panel: Infection Prevention in Post-Acute Long Term Care Facilities

Time: Tuesday, April 29th, 2025, from 10:23AM to 10:34AM

These exceptional presentations showcase the expertise and dedication of our division to pushing the boundaries of infection prevention and clinical care. Be sure to mark your calendar for these sessions—you won’t want to miss the opportunity to learn from these innovative minds!

If you attend one of our sessions, tag us on Bluesky @unmc-id.bsky.social

Let the countdown to SHEA Spring 2025 begin!

Recent Comments