This post is part of a series on Antibiotic Awareness Week 2022, authored by UNMC ID fellow Dr. Mackenzie Keintz. Read on to learn more about growing antimicrobial resistance in the United States and what can be done to stop it.

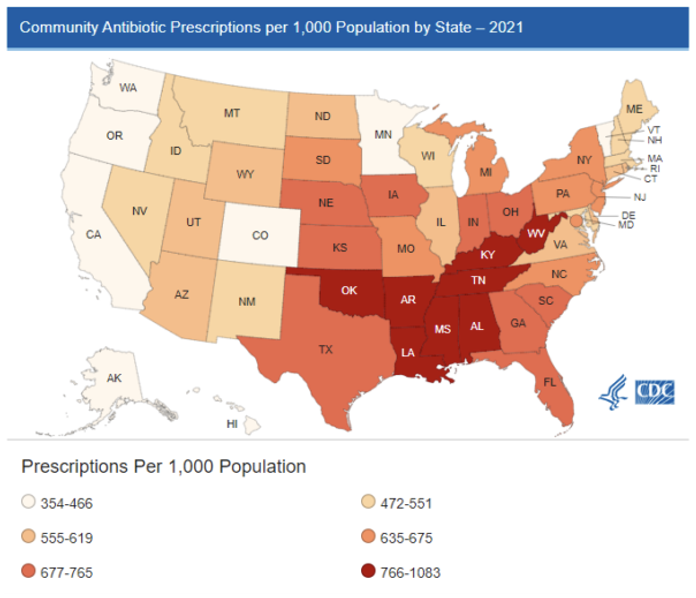

Antimicrobial resistance has been a growing problem within the United States. Antibiotic resistant bacteria are responsible for 2.8 million infections per year and 36,000 deaths per year1. In addition, antibiotic use can be associated with significant adverse events including infections with Clostridium difficile. There are an estimated 223,900 infections resulting in 12,800 deaths1. Outpatient antibiotic prescriptions account for more than half of all antibiotics prescribed. In 2021 this accounted for 211.1 antibiotic prescriptions in the United States, equivalent to 636 antibiotic prescriptions/ 1000 person. Nebraska has one of the highest outpatient antibiotic prescribing rates in the country with 760 prescriptions/ 1000 persons in 20212.

Drivers of inappropriate prescribing

The drivers of inappropriate antibiotic use have been well described. Qualitative studies have evaluated clinician perceptions on antibiotic resistance and inappropriate antibiotic prescribing. Ninety one percent of clinicians interview viewed inappropriate prescribing as a problem within the United States however only 37% thought that inappropriate prescribing was a problem within their own practice7. Without oversight of clinician prescribing, it is difficult for individuals to know how their prescribing rates compare with peer or national averages.

Clinicians often cite diagnostic uncertainty when prescribing antibiotics, including escalating to a more broad-spectrum agent when a narrow spectrum antibiotic would be sufficient, extending the duration, or giving an antibiotic in a clinical situation that it may not benefit8. This is of high concern in the outpatient setting when clinicians have little objective data when making antibiotic prescribing decisions and have an uncertainty regarding patient follow-up.

Many clinicians also cite patient expectation as a reason for inappropriate antibiotic use. They fear damaging the physician-patient relationship if antibiotics are not prescribed when patients expect them. Time constraints also increase inappropriate antibiotic use as clinicians may not feel as if they have time to explain why antibiotics are necessary8.

Qualitative data on patient antibiotic perception has demonstrated that while patients do frequently expect antibiotics, they are willing to defer to a clinician’s judgement on the subject. These studies also showed that although many patients understand that antibiotics do not treat viral infections, they have difficulty distinguishing between viral and bacterial infections. Furthermore, patients may not understand the significant risk of antibiotic use, both individually and for the population9.

Intervention

Interventions to improve antibiotic prescribing in the ambulatory setting should address the root cause of inappropriate antibiotic use which is often not a gap in knowledge. Some institutional implemented strategies that have been shown to be effective include peer to peer feedback, academic detailing, and communication training10-13.

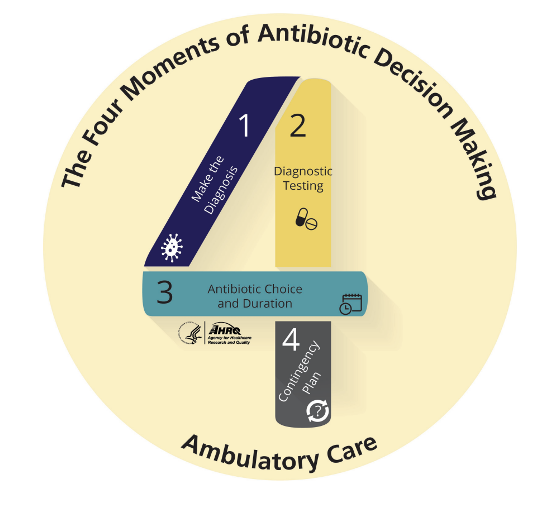

Strategies for individual clinicians to improve their antibiotic use include identifying resources including to guide their antibiotic decision making such as national guidelines. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) suggests a four-time point decision making process that includes:

1. Does my patient have a condition that requires an antibiotic?

2. Do I need to order any diagnostic tests?

3. If antibiotics are indicated what is the narrowest, safest, and shortest regimen I can prescribe? 4. Does my patient understand what to expect and the follow up plan?14

Prescribers can utilize a delayed prescription method to overcome clinical uncertainty. This strategy should not be used in situations in which antibiotics are never indicated, such as bronchitis or viral respiratory infections, but can be helpful in situations where an antibiotic is sometimes required i.e., sinusitis. This allows the physician to have a contingency plan in place for patients that may not wish to return to the office for evaluation if clear instructions are given to the patient15.

One strategy that has been shown to both decrease inappropriate antibiotic prescribing in acute respiratory infections and increase patient satisfaction includes both negative treatment recommendations (antibiotics will not help this viral infection), positive treatment recommendations (this viral infection can be managed symptomatically with xxx), and a contingency plan (if symptoms are not better in a week or have double worsening antibiotic plan can be revisited)16. In addition to education from individual clinicians, other efforts have been made on a national scale to educate patients about the risk of using antibiotics when not indicated, through campaigns like Be Antibiotic Aware by the CDC. During Antibiotic Awareness Week, think about how you can incorporate the 4 moments of antibiotic decision making into your clinical practice.

Resources for Clinicians

CDC Adult Outpatient Treatment Recommendations

Adult Outpatient Treatment Recommendations | Antibiotic Use | CDC

Pediatric Outpatient Treatment Recommendations | Antibiotic Use | CDC

AHRQ Toolkit to Improve Antibiotic Use in Ambulatory Care; Includes educational guidance and communication skill strategies

CDC Antibiotic Awareness; Includes educational resources for clinicians, patients, and printable resources

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2019.” https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/pdf/threats-report/2019-ar-threats-report-508.pdf. Accessed November 4 2022.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Outpatient Antibiotic Prescriptions- United States, 2019.” https://www.cdc.gov/antibiotic-use/data/report-2019.html. Accessed November 4 2022.

- Sanchez, Guillermo V. et al. “Core Elements of Outpatient Antibiotic Stewardship.” https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/rr/rr6506a1.htm. Accessed Novemeber 4 2022.

- The Joint Commission. Antimicrobial Stewardship in Ambulatory Health Care. Accessed November 4, 2022. https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/standards/r3-reports/r3_23_antimicrobial_stewardship_amb_6_14_19_final2.pdf

- Fleming-Dutra, K. E. et al. “Prevalence of Inappropriate Antibiotic Prescriptions among Us Ambulatory Care Visits, 2010-2011.” JAMA, vol. 315, no. 17, 2016, pp. 1864-73, doi:10.1001/jama.2016.4151.

- Shively, N. R. et al. “Prevalence of Inappropriate Antibiotic Prescribing in Primary Care Clinics within a Veterans Affairs Health Care System.” Antimicrob Agents Chemother, vol. 62, no. 8, 2018, doi:10.1128/AAC.00337-18.

- Zetts, R. M. et al. “Primary Care Physicians’ Attitudes and Perceptions Towards Antibiotic Resistance and Antibiotic Stewardship: A National Survey.” Open Forum Infect Dis, vol. 7, no. 7, 2020, p. ofaa244, doi:10.1093/ofid/ofaa244.

- Sanchez, G. V. et al. “Effects of Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Primary Care Providers on Antibiotic Selection, United States.” Emerg Infect Dis, vol. 20, no. 12, 2014, pp. 2041-7, doi:10.3201/eid2012.140331.

- Spicer, J. O. et al. “Perceptions of the Benefits and Risks of Antibiotics among Adult Patients and Parents with High Antibiotic Utilization.” Open Forum Infect Dis, vol. 7, no. 12, 2020, p. ofaa544, doi:10.1093/ofid/ofaa544.

- Milani, R. V. et al. “Reducing Inappropriate Outpatient Antibiotic Prescribing: Normative Comparison Using Unblinded Provider Reports.” BMJ Open Qual, vol. 8, no. 1, 2019, p. e000351, doi:10.1136/bmjoq-2018-000351.

- Solomon, D. H. et al. “Academic Detailing to Improve Use of Broad-Spectrum Antibiotics at an Academic Medical Center.” Arch Intern Med, vol. 161, no. 15, 2001, pp. 1897-902, doi:10.1001/archinte.161.15.1897.

- Gjelstad, S. et al. “Improving Antibiotic Prescribing in Acute Respiratory Tract Infections: Cluster Randomised Trial from Norwegian General Practice (Prescription Peer Academic Detailing (Rx-Pad) Study).” BMJ, vol. 347, 2013, p. f4403, doi:10.1136/bmj.f4403.

- Cals, J. W. et al. “Evidence Based Management of Acute Bronchitis; Sustained Competence of Enhanced Communication Skills Acquisition in General Practice.” Patient Educ Couns, vol. 68, no. 3, 2007, pp. 270-8, doi:10.1016/j.pec.2007.06.014.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. “Four Moments of Antibiotic Decision Making.” https://www.ahrq.gov/antibiotic-use/ambulatiry-care/four-moments/index.html. Accessed November 16, 2022.

- Spiro, D. M. et al. “Wait-and-See Prescription for the Treatment of Acute Otitis Media: A Randomized Controlled Trial.” JAMA, vol. 296, no. 10, 2006, pp. 1235-41, doi:10.1001/jama.296.10.1235.

- Mangione-Smith, R. et al. “Communication Practices and Antibiotic Use for Acute Respiratory Tract Infections in Children.” Ann Fam Med, vol. 13, no. 3, 2015, pp. 221-7, doi:10.1370/afm.1785.