The COVID-19 pandemic has changed lives all over the world, responsible for over 4 million infections and over 300,000 deaths worldwide. As we have progressed through this pandemic, it has become clear in the United States that we need to begin and continue conversations relating to the disturbing racial/ethnic disparities we are seeing emerging from cases, hospitalizations, and death due to COVID-19. We have identified risk factors for severe disease, developed multiple testing modalities, and tested several treatment options. It is time to address the generational inequities that have allowed these health disparities to exist.

Disparities exist

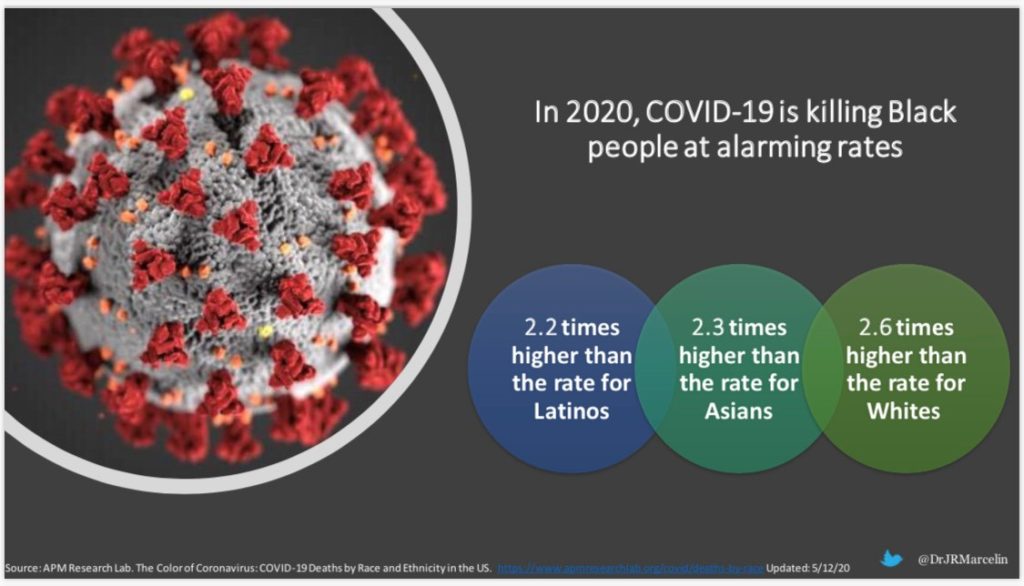

With more than 80,000 deaths in the US, we are seeing higher rates of infection, hospitalizations, and death among African Americans, Hispanic Americans, and Native Americans. In certain states, these disparities are even wider; for example in Wisconsin and Kansas, Black residents are seven times more likely to die from COVID-19 than White residents; in Washington DC, the rate is six times higher, in Michigan five times higher, and in NY four times higher. In New York City, a disproportionate number of people dying from COVID-19 are Hispanic (Source: APM Research Lab). Navajo Nation (the largest community of Native Americans living on tribal homelands across Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah) has more coronavirus cases per capita than any US state.

Where does Nebraska stand?

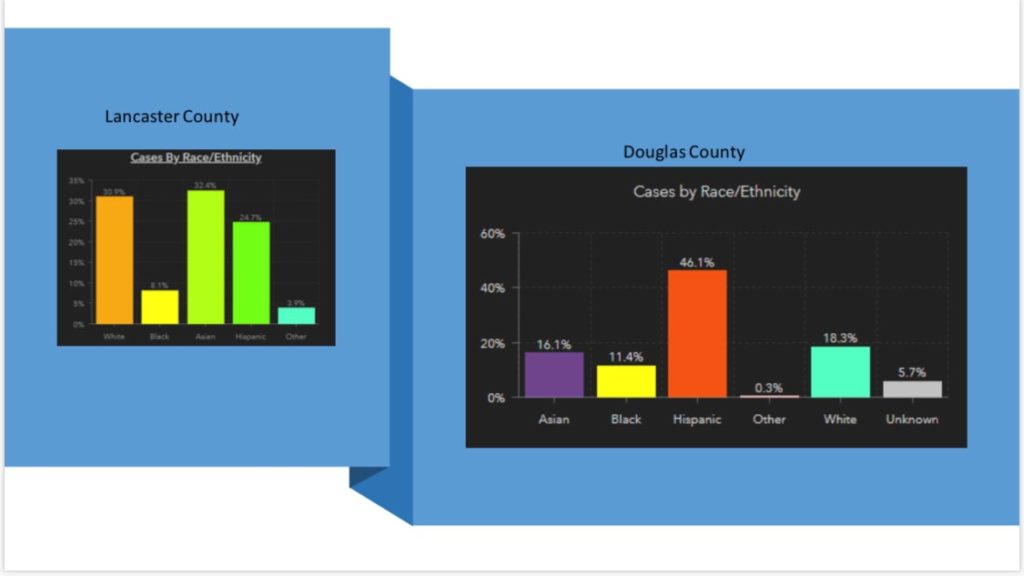

Here in Nebraska, over 10,000 people have been diagnosed, and over 120 people have died from COVID-19. However, Nebraska is the only state that is not only NOT reporting ANY demographic data at all about cases, so there’s no way we would be able to know race data at all on a statewide level. We do have demographic data from Douglas County and Lancaster County, where we see disproportionate numbers of cases in the Hispanic and Asian populations. In Douglas County, almost 50% of reported cases are among Hispanic persons, and 16% of reported cases are among people of Asian descent (that includes large Nepali immigrant/refugee communities). In Lancaster County, 33% of cases reported are among people of Asian descent, and 24% among Hispanic people. We are seeing these disparities play out in real time in our hospital, as a large number of our patients in COVID-19 units are minority and/or immigrant people.

Why is this happening?

There are social, economic, and political structures embedded in our society that interact to create structural/social determinants of health, which in turn impact health outcomes. One cannot discount the disparities in the underlying medical conditions associated with higher risk of severe COVID-19. Heart disease, obesity and diabetes are risk factors for more severe disease and death, and these conditions are overrepresented in the Black, Hispanic, and Native American communities relative to their share of the population. However, generational patterns in development of these comorbidities is not proof of a purely biological explanation for the disparities.

What we are witnessing is the impacts of structural racism (systems that perpetuate and reinforce racial inequities) on minoritized communities. The differences we are seeing are a manifestation of the systemic differences in food insecurity, housing insecurity, financial insecurity, lack of access to healthcare, lower quality healthcare, and inability to shelter at home, that predispose these minority groups to have worse health outcomes. The virus, SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 is NOT Racist. However, societal structural racism plays a significant role in creating conditions that put minority communities at risk.

What needs to be done now?

There needs to be a structured, coordinated effort to collect and report data here in Nebraska (and more completely across the country) on COVID-19 that includes demographics. This will help with creating targeted testing strategies in communities that are most at risk. In Nebraska, we have several immigrant populations whose first language is not English, therefore as healthcare professionals and an organization, we must ensure that we are helping to provide communication/education in a culturally congruent manner. If a language does not have a reliable written component or most people cannot read, we must be innovative with videos, television, social media, and personal community outreach in the language that people understand. Couldn’t we leverage our own healthcare professionals who speak different languages to help with this?

In the long term, there are many more things that need to be done to address the impacts of structural racism in the community. Dealing with these will help to ensure that the next time we are dealing with a pandemic or major health crisis in our nation, we will not be talking about these kinds of disparities.

Want to learn more?

Here are some recent opportunities to hear or read more about this topic:

• North Omaha Information Support Everyone (NOISE) Facebook Live April 30,2020

• UNMC Internal Medicine Grand Rounds presentation May 8, 2020

• Infectious Diseases Society of America Podcast published May 12, 2020

• Omaha World Herald Opinion piece (co-authored with UNMC medical student Rohan Khazanchi) published May 14, 2020

Peer-reviewed references included in this post:

- Essien U and Venkataramani A. Data and Policy Solutions to Address Racial and Ethnic Disparities in the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Health Forum, April 2020

- Chowkwanyun M, and Reed AL. Racial Health Disparities and Covid-19 — Caution and Context. N Engl J Med. May 2020

- Krieger N et. al. The Fierce Urgency Of Now: Closing Glaring Gaps In US Surveillance Data On COVID-19. Health Affairs Blog, April 2020.

- Haynes N et. al. At the Heart of the Matter: Unmasking and Addressing COVID-19’s Toll on Diverse Populations. Circulation, May 2020

Here is a list of selected publications you can access to learn even more

As a Latina, I have to say this is very unfortunate. Thanks, for the very well written piece.