We are always excited to have our ID fellows provide guest blog posts. Second year ID fellow Dr. Lindsey Rearigh (follow her on Twitter @LRearigh) was recently on her Antimicrobial Stewardship rotation and reviewed the latest published guidelines for Community-Acquired Pneumonia (CAP).

We are always excited to have our ID fellows provide guest blog posts. Second year ID fellow Dr. Lindsey Rearigh (follow her on Twitter @LRearigh) was recently on her Antimicrobial Stewardship rotation and reviewed the latest published guidelines for Community-Acquired Pneumonia (CAP).

The American Thoracic Society (ATS) and Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) recently released updated community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) guidelines. The first immediate implication is the healthcare-associated pneumonia (HCAP) definition is gone for good. IDSA had previously retired the term in the 2016 hospital-acquired pneumonia/ventilator-acquired pneumonia (HAP/VAP) guidelines.

HCAP was previously defined as patients with any one of the following risk factors: residence in a nursing home or other long-term care facility, hospitalization for >/= 2 days in the last 90 days, receipt of home infusion therapy, chronic dialysis, home wound care or a family member with a known antibiotic-resistant pathogen. This category would help guide empiric antibiotic therapy (before an organism is known), which could include treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and other multi-drug resistant pathogens.

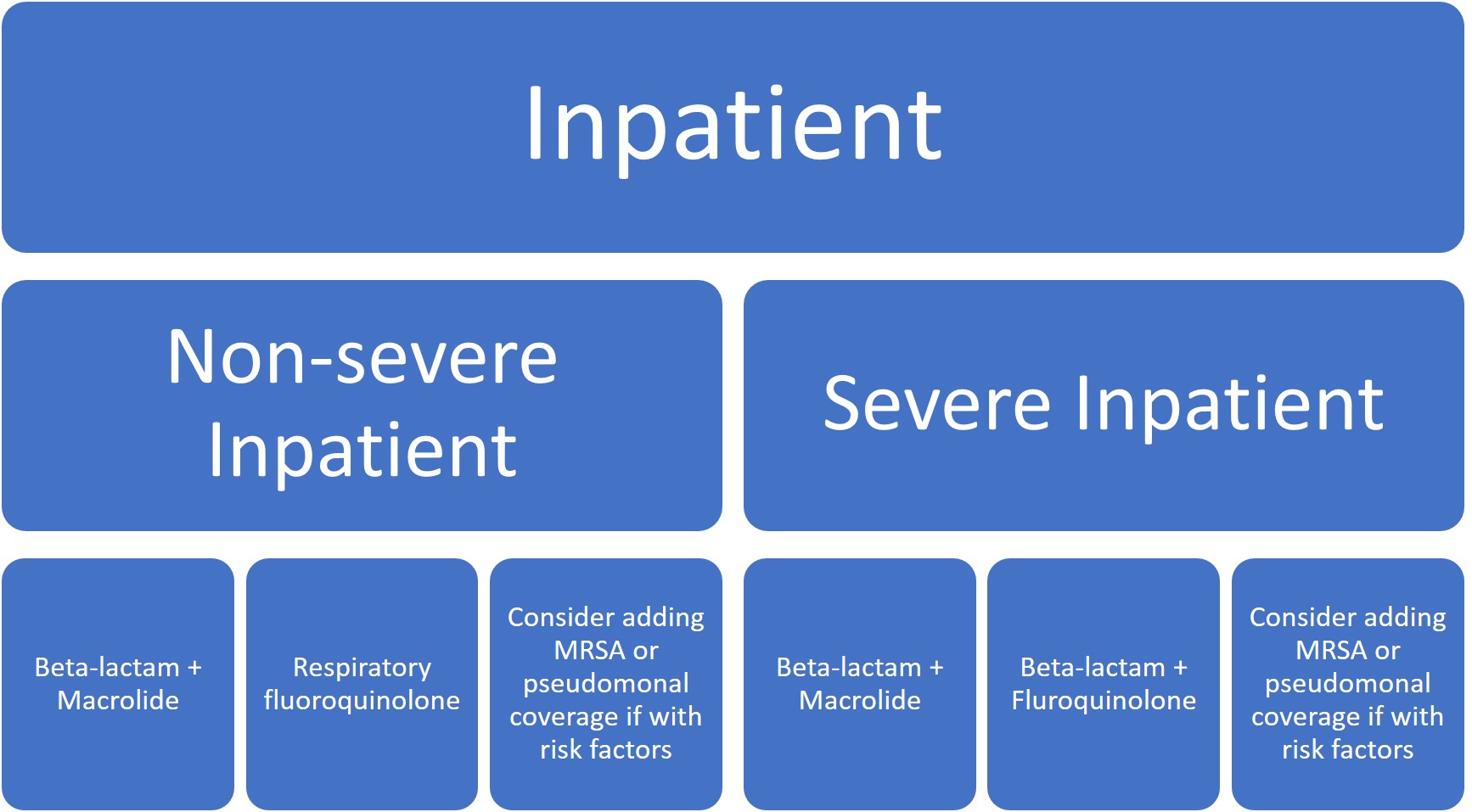

In these new guidelines, clinicians are now recommended to empirically treat for MRSA or P. aeruginosa in adults with CAP only if locally validated risk factors for either are present. The most consistently strong individual risk factors for MRSA/P. aeruginosa include previous lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) with MRSA or P. aeruginosa, hospitalization within last 90 days, or if the patient had received intravenous (IV) antibiotics within that time-frame. If empiric MRSA or P. aeruginosa therapy is started, the guidelines recommend de-escalation at 48hrs if cultures remain negative.

Traditional pathogens that previously accounted for CAP included Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Legionella species, Chlamydia pneumoniae and Moraxella catarrhalis. Now with the implementation of vaccinations, viral pathogens are thought to be more prominent causes of CAP. Streptococcus pneumoniae is still a major contributor, although declined from 90-95% to 5-15% in recent studies.

Other main updates fall into the realm of diagnostic stewardship. The guidelines do not recommend obtaining sputum and blood cultures in the outpatient or inpatient setting, except only in cases of severe CAP (admission to the ICU or intubated), or if the patient is being empirically treated for MRSA or P. aeruginosa.

Procalcitonin has previously been used to help guide clinicians in the initiation of antibiotics in LRTI, but there were concerns of varied sensitivity of the test (range 38-91%) might miss patients with bacterial causes. The guidelines recommend empiric antibiotic therapy for presumed CAP regardless of initial serum procalcitonin.

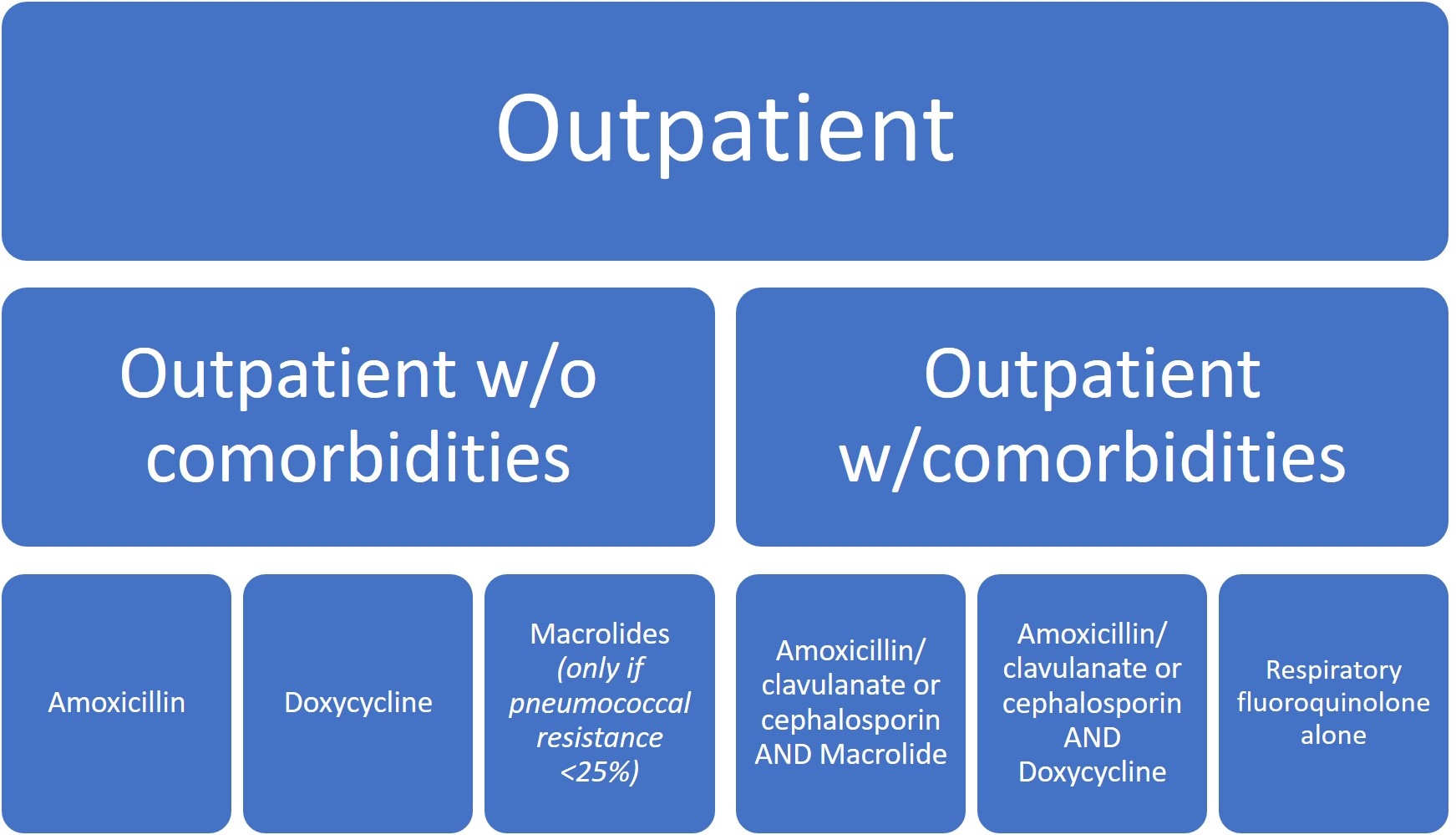

Given the rising incidence and prevalence of viral causes of CAP, more research is needed to accurately identify clinical scenarios where antibiotic therapy can be safely withheld. Overall, treatment recommendations have not significantly changed except for the de-emphasis on macrolide monotherapy, particularly in areas where macrolide resistance was >/= 25% (which is pretty much everywhere in the US).

Five days of therapy is recommended to be adequate given the patient has reached clinical stability, including normalization of vital signs, ability to eat, and returned to baseline mental status.

Five days of therapy is recommended to be adequate given the patient has reached clinical stability, including normalization of vital signs, ability to eat, and returned to baseline mental status.

If you are looking for a longer play-by-play summary of the new guidelines on Twitter, including a robust discussion of the mention of ceftaroline for CAP, click here for a thorough assessment by @ASPphysician, Dr. Andrew Morris.

Great review Lindsey. The guidelines unfortunately do not address a key problem in pneumonia, its diagnosis, which is challenging and difficult. Misdiangosis of pneumonia is common and results in frequent use of unnecessary antibiotics. The guide authors make all recommendations from a point of 100% confidence in the diagnosis of CAP and the guidance should be viewed in that light. In patients where diagnostic uncertainty exists as to the pneumonia diagnosis (which is much more common) the use of markers like procalcitonin can be helpful and the routine use of antibiotics in patients with influenza may not be necessary.