This post is part of an ongoing series on HIV/AIDS in recognition of HIV/AIDS awareness month 2022. In this series, we focus our posts on education, research, achievements, and medicine pertaining to the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

Today, we start a new series of posts on the UNMC ID Blog: Microbe Monday. This is a monthly installment introducing the microbiology behind the pathogens routinely encountered in the clinic. While these posts are geared more towards education, recent research advances and interesting historical context should be broadly interesting to all readers. Our first microbe is the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Read on to learn more about this important pathogen.

HIV

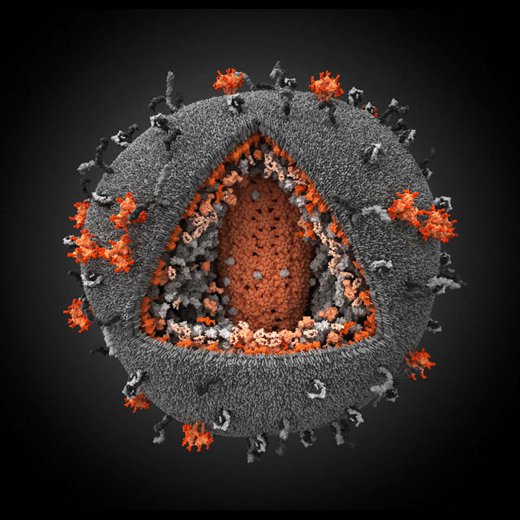

HIV is what is known as a retrovirus. This class of virus have the unique ability to convert its genetic material into DNA, much like the DNA that exists in human cells. Once this happens during infection, the viral DNA can hide within human DNA and evade detection for a period of months to years. This is also why HIV is so difficult to cure, with only a handful of cases ever reported. Functionally, there is no current cure for HIV, but this is an active field of research and there are many extremely effective treatments which have revolutionized the medicine of HIV care.

Advanced HIV results in an acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (also known as AIDS). In this syndrome, advanced HIV leads to severe immune system damage and increased susceptibility to multiple different cancers and infection by opportunistic pathogens (microbes which normally do not cause disease in healthy people, but thrive in those with compromised immune function). Advanced HIV is defined when a person with HIV has a reduced CD4 T-cell count (a specific type of immune cell), or diagnosis with one of these cancers or opportunistic infections, even without identified immune dysfunction.

Macrophages, T-cells, nooks and crannies

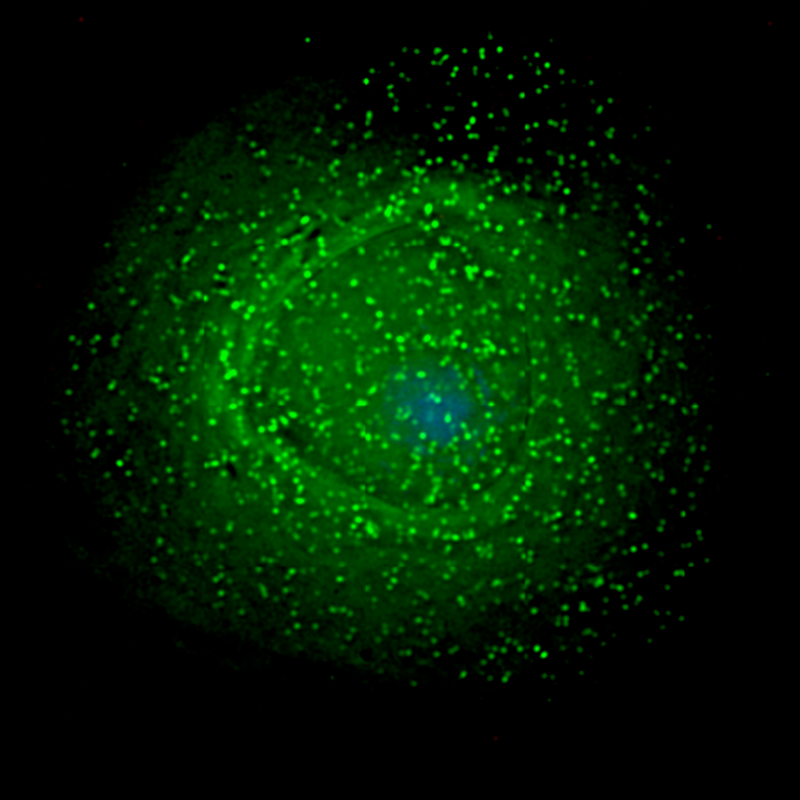

HIV is first thought of as an infection of T lymphocytes (T-cells), as these are the cells that clinicians use to characterize the severity of HIV infection. T-cells are specialized immune cells responsible for controlling many different aspects of your immune system. They come in two flavors: CD4 and CD8. CD4 T-cells are the primary target of HIV, which is important because these cells act as your immune system’s ‘generals’, coordinating the rest of your immune system to fight infections or cancers. It makes sense then that as these cells start to decline, people with HIV (PWH) start to become increasingly susceptible to infections and malignancy.

However, it has been recently shown that this virus also infects other cell types. The most recognized example of this is HIV infection of macrophages. These cells are essential components of the ‘front lines’ of the immune response and are present in almost every part of the body. More recent research suggests that there may be additional cellular reservoirs where this virus may hide. Some emerging evidence point to certain types of glia, your brain’s supporting cells, which may inadvertently shield this virus from attack from the immune system or certain antiviral drugs (see this paper and others for further reading). But this is far from settled science, and there is much we still do not know about the mechanics of HIV infection.

Symptoms, Treatment, and Prevention

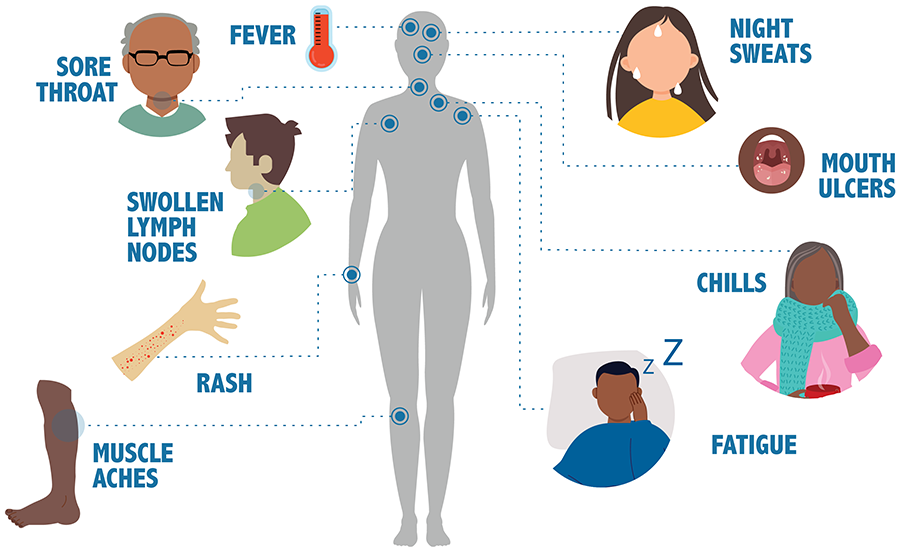

The symptoms of HIV infection are unique from most viral infections. In the days and weeks following initial infection, 50-90% of infected individuals will experience a strong flu-like illness, with symptoms like fever, swollen lymph nodes, sore throat, rash, muscle and joint aches and pains, and fatigue. This acute infection quickly resolves as your immune system fights off the initial wave of HIV infection. At this point, the virus goes dormant for a period of months to years where is slowly depletes CD4 T-cell levels with few identifiable symptoms. This continues until the disease becomes advanced, meaning CD4 levels are low enough to lead to opportunistic infection or cancer. Clinical outlook for PWH who remain undiagnosed and/or untreated is poor, with most reaching complete T-cell depletion by 5-10 years after initial infection.

Fortunately, we have many very effective tools to fight these infections in the form of antiretroviral drugs. The way these drugs work varies, but all of them impede the ability of HIV to replicate itself. If treatments are taken consistently and life-long, undetectable HIV viral loads are not only possible, but clinically expected. Importantly, PWH who have undetectable HIV viral loads are unable to transmit the virus to others. This knowledge is the basis of the U=U (undetectable = untransmittable) campaign.

While treatment of HIV has been revolutionized since the onset of the epidemic, this infection remains incurable, making prevention the best medicine. Three main approaches are used currently to improve preventive measures in the population. First, public education with science-backed information is of prime importance. There are preventative measures that can be taken by those at risk of HIV that forms an important first barrier to spreading this infection. Second, since someone can be unknowingly infected with HIV for many years before diagnosis, routine testing is a powerful way to support one’s own and the community’s health. Lastly, certain medications can be prescribed for prevention called PrEP (Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis), when taken regularly, can reduce the risk of contracting HIV by 99%, providing an additional layer of protection to those who may be exposed to HIV. Additionally, the U=U campaign means that if we can initiate and maintain every person with HIV on antiretroviral treatment with an undetectable viral load, this can also significantly contribute to the prevention of onward transmission of HIV.

Conclusion

HIV is serious pathogen and an important consideration for public health. It has been just over 40 years since the first case of AIDS was diagnosed in the United States (June 1981). In this short period of time, advancements in research and clinical practice have dramatically changed the outlook for PWH. Proper use of preventive and treatment measures along with continued support for research on HIV/AIDS has the promise to continue to accelerate our ability to fight this infection.

If you are interested in HIV education, testing, treatment, or care and/or think you may be at risk of HIV infection, check out the Nebraska Medicine Specialty Care Center, free testing at the RESPECT clinic and through the Nebraska Department of Health and Human Services, and contact your primary care provider.

References

Brock, T. D., Madigan, M. T., Martinko, J. M., & Parker, J. (2003). Brock biology of microorganisms. Upper Saddle River (NJ): Prentice-Hall, 2003.

Deeks, S., Overbaugh, J., Phillips, A. et al. HIV infection. Nat Rev Dis Primers 1, 15035 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2015.35

Centers for Disease Control (CDC), HIV.gov, and linked webpages throughout