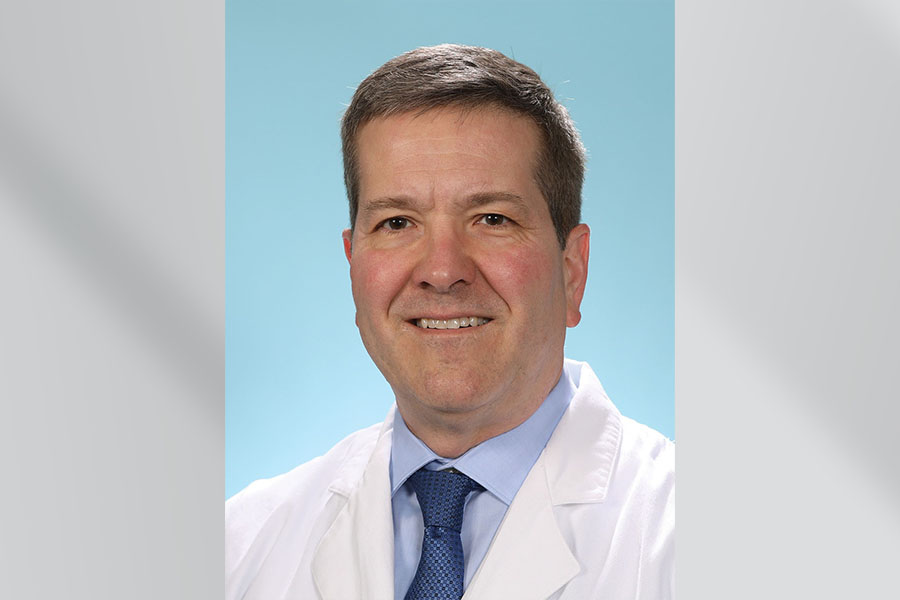

Dr. Mohanad Al-Obaidi joins UNMC ID as an associate professor coming from University of Arizona in Tucson. His expertise is in care of immunocompromised patients with infections, and fungal infections. Read on to learn more about the newest member of our ID division. Welcome Dr. Al-Obaidi!

Tell us a little about your background in medicine.

I am originally from Baghdad, Iraq, where I completed my medical degree at the University of Baghdad. I moved to the United States and completed my internal medicine residency at Texas Tech University before pursuing infectious diseases training at the MD Anderson and the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. I got interested in infectious diseases during my internal medicine residency, but I developed an interest in the topics of fungal infections and infections in the immunocompromised hosts during my ID fellowship training in Houston. So, after completing my ID fellowship training, I pursued more training in transplant infectious diseases at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. Afterward, I worked the University of Arizona College of Medicine in Tucson as a faculty member and worked in the transplant infectious diseases services for the last 7 years, before moving to Omaha. During that time, I continued my passion in clinical research of infections in the immunocompromised patients and fungal infections.

Tell us about your new position.

I joined the division of infectious diseases at UNMC in October of 2025 as an associate professor, working in the SOT and oncology infectious diseases services. I plan to continue delivering evidence-based and up-to-date care to immunocompromised patients. I am also working on continuing my research interests that can translate and benefit patient care by advancing the current knowledge of infectious diseases among immunocompromised patients.

Why did you want to work at UNMC?

UNMC has a remarkable history of delivering cutting-edge medical care and is renowned for its pioneering clinical research endeavors. I was drawn to UNMC and the division of infectious diseases because of the faculty’s well-known background and extensive expertise in clinical care and research fields. Also, moving to Omaha, Nebraska, brought us closer to family members.

What about ID makes you excited?

I am drawn to solving new challenges and learning new things, and infectious disease is a fascinating specialty that always brings new and challenging cases to tackle. It also requires knowledge of the intricate complexities of human health and understanding different aspects of human pathophysiology. Moreover, working in transplant infectious disease allows me to collaborate with brilliant colleagues in the transplant field, fostering a comprehensive and multidisciplinary approach to patient care.

Tell us something interesting about yourself unrelated to medicine.

I enjoy reading (or listening to) science fiction books, particularly classics like Isaac Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke, and I also enjoy discovering new sci-fi books. I also love spending time with my family and creating memorable experiences for our child. We enjoyed backpacking the outdoors in Arizona, and hiking/exploring national parks.

You can find Dr. Al-Obaidi’s research and publications on PubMed

Recent Comments