This guest blog post is written by Dr. Tatia Hardy, a graduating PGY4 Internal Medicine/Pediatrics resident at UNMC. Dr. Hardy wanted to share her reflections on racism as a public health crisis, looking through the historical lens of the Tuskegee syphilis experiment.

A tradition in many medical schools in the United States is a ceremony where incoming students recite the Hippocratic Oath. Within that creed are words that are habitually considered and sometimes recited when making decisions regarding patients’ care: “first, do no harm.” Contrary to our oath, the realm of medicine has played an active role in the long history of harm and oppression of Black people in the United States.

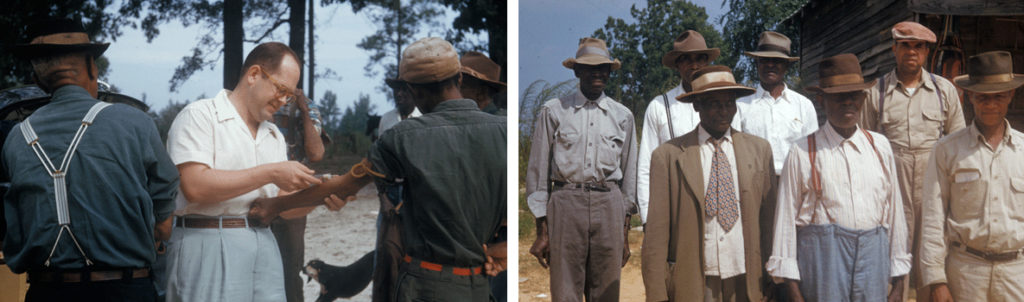

In 1932, the United States Public Health Service (PHS) embarked on what would become one of the most famous examples of the country’s medical maltreatment of the Black community. Lured by the promise of free medical care, six hundred Black men in Macon County, Alabama, initially enrolled in the Tuskegee syphilis study. The men were told they would be treated for “bad blood,” a term used in the South that encompassed a number of ailments, including syphilis and anemia. The 399 enrolled men found to have syphilis were not told of their diagnosis, despite the risk of spread to others. Syphilis was known to be associated with significant morbidity and mortality at the start of the study.

In the first half of the 20th century, physicians attempted to treat syphilis with various agents because of the known dangers of the disease. The therapies used were risky and not always effective. A window in a basement lab had been left open years prior to the start of the Tuskegee study, giving Sir Alexander Fleming the opportunity to introduce the world to a new drug called penicillin. This new drug could not be produced in large quantities until the mid-1940s and would not become standard treatment of syphilis until 1947.

When the United States entered World War II, 250 of the men involved in the study registered for the draft. As part of the physicals done prior to entry into the armed forces, the men were diagnosed with syphilis and ordered to get treatment. Researchers from the PHS intervened and prevented the men from getting treated. The study was originally intended to last six months but was still going on when penicillin was recommended for the treatment of syphilis in 1947. Despite the availability of a medication to cure the disease, the men in the study were not offered treatment. In fact, they had been misled to believe they had been treated in the course of the study; they were given placebos and subjected to non-therapeutic procedures such as lumbar punctures.

Objections to the study were raised in the 1950s and 1960s by individuals concerned about the ethics of the study. Action wasn’t taken until 1972 when a PHS researcher got information to a reporter with the Associated Press. Public outcry from the nationally published article prompted swift action to stop the study and investigate. By that time, only 74 of the original 399 men with syphilis were still alive; 28 had died of syphilis and 100 died of complications related to syphilis. Forty wives of the study participants were infected, and 19 infants were born with congenital syphilis.

Photo credit: UNMC/Nebraska Medicine

When learning about historical events, particularly those that are tragic and preventable, there is a tendency for introspection: “what would I have done? Would I have been brave enough to do the right thing?” Physicians involved in the Tuskegee study stood by as their research subjects suffered from the devastating effects of syphilis. As physicians in 2020, we must recognize that we are still in the midst of a public health crisis. Racism has broad consequences and adversely affects the health and well-being of Black men, women, and children.

For me personally, my interests in medicine, public health, and social justice intersect in the domain of prison medicine. Having privilege meant that I didn’t ever have to think or worry about being arrested in school, no matter how disruptive I was. I plan to continue learning about how to dismantle the school-to-prison pipeline and advocate for better resources for justice-involved youth and their families. I plan to use my knowledge of the studies regarding adverse childhood experiences to advance legislation aimed at community improvement – providing funding and resources to areas of need.

On a smaller scale, I want to listen to and support my Black colleagues in medicine: physicians, nurses, students, and ancillary staff. I plan to engage medical students and residents in more frank discussions about racism and how it contributes to health disparities. I will encourage my co-residents in Internal Medicine and Pediatrics to consider taking a course called “Institutional Oppression” from the University of Nebraska Omaha. I will vote, and as the leader of my medical team, I will do everything possible to make sure those around me have an opportunity to leave the hospital or clinic to vote.

When this chapter of history is studied in the future, will we be proud of what we’ve done? Are we brave enough to do the right thing? We must uphold our Hippocratic oath to first do no harm. But we also have an opportunity and a responsibility to be active in ending systemic racism.

References:

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). “U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee.”

Gamble, VN. (1997). “Under the shadow of Tuskegee: African Americans and health care.” American Journal of Public Health. 87(11): 1773-1778.

Heller, J. (1972). “Syphilis victims in U.S. study went untreated for 40 years.” New York Times.

Nix, E. (2017). “Tuskegee experiment: The infamous syphilis study.” History Channel