I didn’t know what to expect – clocks drawn by Alzheimer’s patients?

OK.

Arranged into an exhibition by one of our first-year anesthesiology residents?

Odd, but OK.

I was surprised at how all the pieces fell together and made sense as I learned more about the resident, Andy Peck, M.D., and saw his exhibit.

We talked as our photographer, Rich Watson, snapped photos at the Artists’ Cooperative Gallery, 405 S. 11th St., where Dr. Peck – “call me Andy” – gathered the drawings into an exhibition, “10 till 2: Alzheimer’s in Omaha.”

The exhibit, which actually forms a clock face with the time – 10 till 2, is meant to help viewers see through the eyes of someone with Alzheimer’s disease.

“Alzheimer’s doesn’t get talked about like heart disease and September is Alzheimer’s Awareness month,” he said.

Andy wanted to give Omaha something to consider.

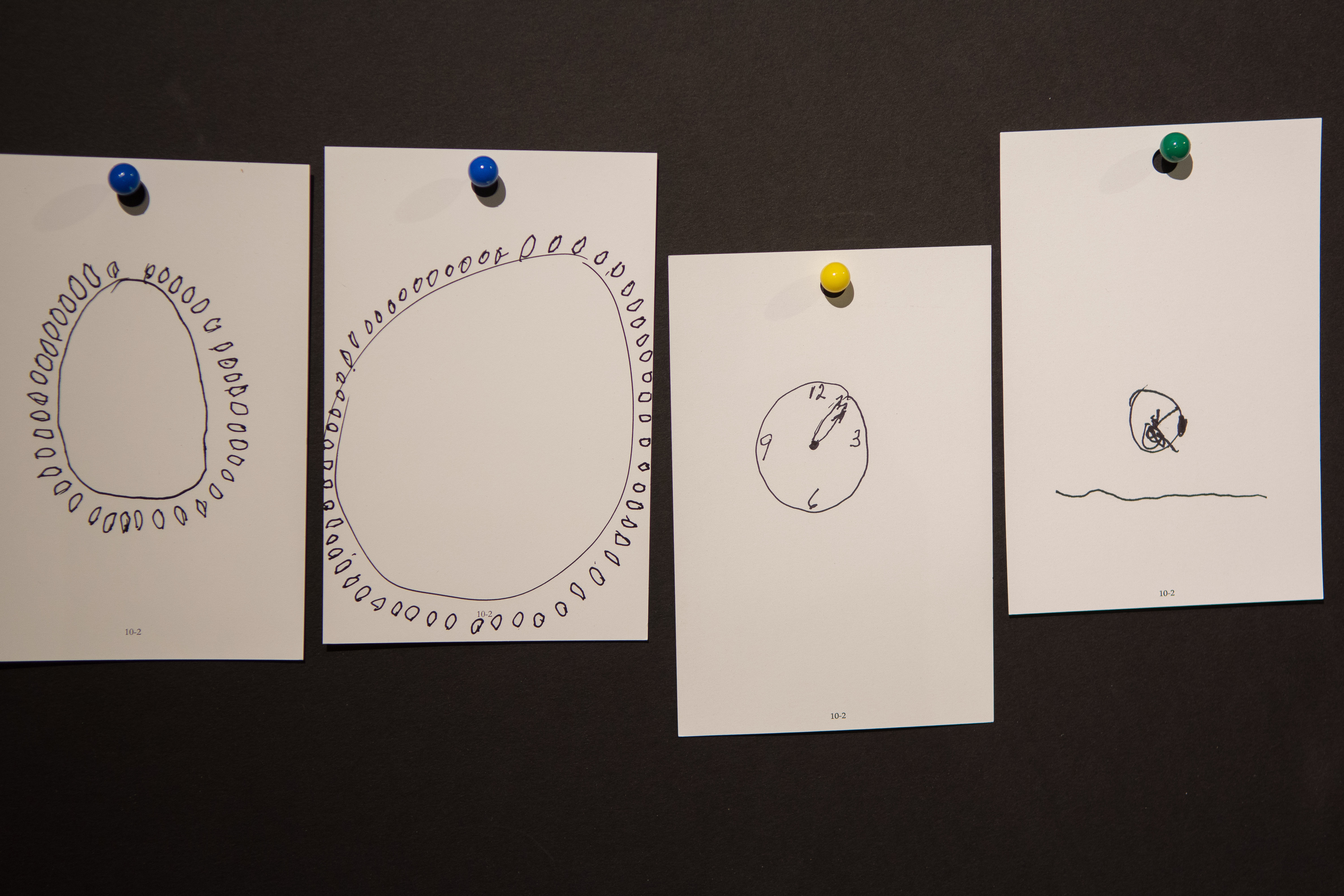

The drawings are shocking and powerful.

Few of the nearly 150 drawings in the exhibit show the correct time. Some don’t even resemble a clock. Some are well-drawn mantle clocks or Rolex wristwatch faces. Others just have the numbers ‘150,’ some have writing – one in a language Dr. Peck thinks is French.

“There are stories behind these drawings,” he said. “I can still see some of them being drawn. Each piece has power in the space the clocks take on the paper, the lines, like the Salvador Dali piece, “The Persistence of Memory.”

You can see the chaos of the mind.

“Alzheimer’s is a long slow process. First they forget dates and events, then people’s names. They become confused and withdrawn and eventually they have to be put in a care facility. It can tear a family apart deciding what to do,” Dr. Peck said.

He knows. Over the past decade, he watched his grandfather, a dentist in Wisconsin, slowly depart.

“It’s a loss of someone who still lives with you.”

While in medical school at Creighton, he saw one of the clock drawings his grandfather had done and was stunned. “It was very distorted, abstract. I didn’t think he was that far along.”

Dr. Peck had the idea for the exhibit when his grandfather died last spring and a week later he began his new project.

He recruited nurses and employees at long-term care facilities to complete the task with their residents, and he personally performed the test on several people. The procedure: ask residents to draw a clock set at 1:50; encourage, but don’t give assistance.

Quick drawings take about 20 seconds. If unable to recall what a clock looks like or if someone is struggling, it can take a person up to 90 seconds, Peck said. Some are unable to complete the task and leave a scribble or a blank card.

In 2015, there were approximately 48 million people worldwide with Alzheimer’s. The disease process is associated with plaques and tangles in the brain that destroy connections between brain cells. Initial symptoms are often mistaken for normal aging.

There’s no definitive test to diagnose patients while a person is alive.

But, it turns out that since 1968, a series of authors began to describe the use of different types of clock-drawing tests for the identification of dementia. It has become a practical test that clinicians use to screen for cognitive impairment in old age and as a marker to detect dementia or Alzheimer’s.“I don’t think there’s a neurologist that doesn’t use it,” he said.

Dr. Peck’s interest in Alzheimer’s goes back even further than this exhibit. The 26-year-old has been an advocate for the Alzheimer’s Association since 2012. He also served as a board member and team recruitment chair for the 2014 and 2015 Walk to End Alzheimer’s. In 2014, Mutual of Omaha commissioned him to create a public mural in chalk pastel of a diseased brain to promote Alzheimer’s awareness.

Wait, what?

Yes, Andy is an artist too. And a musician. He’s a man with a heart as big as the whole outdoors.

He founded Friends Organizations at Luther College in 2010 during his undergraduate days, and at Creighton University in 2013. It’s a student-led organization charged to support and mentor children with special needs. At Luther, his work earned him the Student Organization of the Year Award in 2012.

He also participates at Special Olympic events and works with the Down Syndrome Alliance. This passion, he said, he got from his mom who teaches special needs children in middle school.

“I’ll always contribute to these two causes,” he said. “You make time for what’s important.”

And, he’s into sports – tennis, golf, swimming (he was a competitive swimmer in college), skiing – and Pickleball, the fastest growing racquet sport.

His goal now is to “be the best physician anesthesiologist I can be.”

Surprisingly, he uses his training as a timpanist to help achieve that goal.

He played the timpani – also known as kettledrums – at Luther. The highlight of his musical career was playing the timpani solo in George Gershwin’s jazzy Piano Concerto in F at the Vienna Opera House during a musical residency in 2012. The concerto’s first movement begins with blasts from the timpani that introduces elements of the main theme.

The timpanist is king of his own province and he is king of his surgical realm. As he would set the drums up in an arc around him, he prepares his drugs and tools for surgery.

“Everything needs to be in its place. The surgeon is the conductor and everyone there is working in concert with the surgeon,” Dr. Peck said.

The grand opening of the Alzheimer’s exhibit drew an impressive 240 people from the community.

“We received positive comments and feedback,” he said.

The exhibit closes Sunday and he hopes to donate it to UNMC or Lasting Hope as a permanent display.

Taking a last look at the exhibit, I notice something different in the center of the clock hands.

On the back of one drawing a spouse wrote:

“The hands of time are wound but once, and no one has the power to know just when the hands may stop — not the day or the hour — so live it with a will, because one day the hands stop!”

That, my friends, says it all.